by Erin C. Healy - Sunday, November 11, 2018

Bob Studley’s first memory is of his father carrying him into the woods. He was 3. His father set him down against a tree and explained that he was going to let their dog go and Bones would flush a rabbit. Then he would shoot the rabbit. He told his son were to watch.

“Everything happened just the way he said it would,” Studley said. “I remember where we were. I could probably point out the tree.”

That memory wasn’t just his first memory of hunting; it was his first memory of life. The fox hound-beagle mix Bones was so famous people would borrow him for their own hunts. Studley’s father taught his son the basics of marksmanship, and when the boy turned 7 he received his own Red Ryder BB gun. During the Depression, neighbors shared their livestock, and because people were out of work, there was time to hunt. Mostly, the quarry was rabbit, pheasant and sea ducks, or coots, a species of scoter. Hunters provided venison, but Studley’s father would not hunt deer himself, telling his son they were “too pretty” to shoot. He did hunt fox, though, for the money the pelts brought in.

Studley grew up in Hanover, Mass., about 25 miles south of Boston, and in 1948 when he was 17 he got his parents’ permission to join the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. After a one-year commitment, he considered a full-time enlistment, but opted for the U.S. Coast Guard instead. He did a year aboard the USCG Cutter (William J.) Duane, which is now an artificial reef south of Key Largo but at the time was an weather ship. Civilians on board studied weather patterns while crewmen listened for Russian submarines. By 1951, in the midst of the Korean War, Studley was checking merchant ships for communists. He attended parachute rigging school through the Navy, learning a skill that would serve him well in the military.

When Studley was 16 he met the woman with whom he would share his life. He and Virginia married when Bob was in the Coast Guard, going on to have five children, 10 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. They celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary before Ginny died in 2017.

Of his military career, Studley said it wasn’t because he necessarily wanted to serve in each branch, but that he wanted to provide what was best for his family at each juncture. As a civilian he worked in a munitions factory that made nose cones for air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles. He also entered the U.S. Navy Reserves as a parachute rigger and served at South Weymouth Naval Air Station. When the government munitions contract expired, Studley parlayed his Reservist position into a full-time enlistment in the U.S Air Force, losing rank but gaining steady work close to home on Otis Air Force Base on Cape Cod. The Air Force was Studley’s fourth branch of service and the one from which he would retire.

Studley did find time to hunt but his main focus was on work and his growing family. The family spent three years at Sewart Air Force Base in Tennessee, and then in 1961 Studley got the duty station of a lifetime: Ladd Air Force Base in Fairbanks, Alaska. To get there Studley drove the ALCAN (Alaska-Canada) Highway and was awe-struck by the natural beauty surrounding him. When survival instructors at the Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory put out a request for volunteers, Studley jumped at the chance. The lab researched the effects of cold weather and water on people, animals, vehicles and equipment.

Studley learned to build igloos and other snow shelters for outdoor survival. He live-trapped ground squirrels and snowshoe hares for laboratory use, participated in the dog-sledding program and was a thermal stress subject for numerous experiments both at the lab and throughout Alaska. The most memorable being a simulated survival trip down the Colville River, along the Arctic Slope to the Arctic Coast some 100 miles distant.

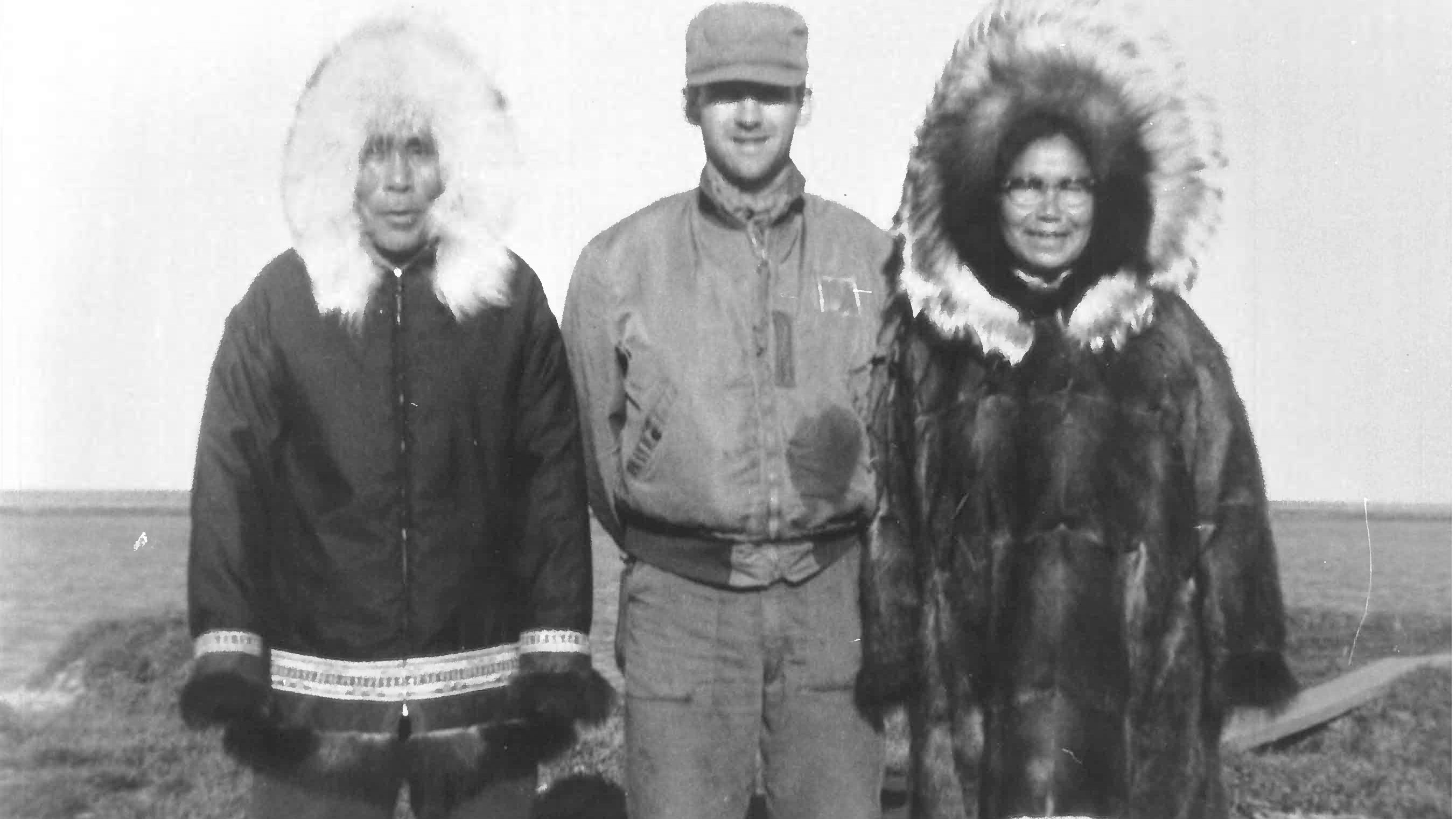

The trip started in Umiat, where Studley and Captain J. E. Veghte had theoretically bailed out of an aircraft and would now attempt to survive using only what they had on them. Veghte had a .357 magnum and Studley had a .22 magnum, in addition to each carrying a small survival kit and a one-man life raft attached to their parachute harnesses. They ate ground squirrels that they took by handgun. The meat tasted like the willows the squirrels fed on. The terrain was merciless. Simply climbing down a ravine for water was so arduous that the men would be thirsty before they even returned. The men got progressively weaker. To conserve energy they decided to make a flotation devise using their survival rafts, and for safety sake, tied them together with a barrel in the middle. The U. S. Navy had staged barrels in the area for use in oil exploration. In a real survival situation, the men would have made a permanent camp, but they had two weeks to get to the mouth of the river for a rendezvous with a helicopter. They arrived two days early, though, and were surprised to find an Eskimo couple living there, who stuffed them with caribou and fish.

“You could take three caribou,” Studley remembers of regulations at the time. He remembers bagging one for himself and another for a friend. Later, he was near a man who took a shot but was too close to his scope. The recoil tagged him, delivering a nasty cut above his eye. Studley rendered first aid and then asked the man if he wanted him to shoot one for him. The man said yes and Studley soon obliged. Having taken his three, he walked into the woods and watched a herd walk by. He was surprised by the size of the animals, regretting that he hadn’t waited. They moved less than a yard from where he hid behind a fir tree. “I thought about poking one with my rifle,” he said. “I didn’t, but it would have been like counting coup, like the Indians did.” The practice carried the prestige of the conquest without killing the enemy.

It was visceral experiences like this that prompted Studley to request a duty extension, but was turned down. Packing the car to leave, he tried not to let his eldest son see him cry.

Studley went on to focus on marksmanship, become the 124th airman to earn the prestigious Distinguished Rifleman Badge. Back on Otis, from July 1965 until his retirement in 1970 as master sergeant and non-commissioned officer in charge of the base’s small arms marksmanship section, he trained airmen for annual marksmanship qualification and others who were heading to Vietnam. He then began a 22-year career as an environmental police officer with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Even when he retired for the second time, Studley continued to teach firearms safety through the National Rifle Association and became a hunter education instructor. Even into his 80s he continues to train civilians for their permit and retired law enforcement officers for their permit to carry out of state.

But whether on a rabbit hunt with his dad at 3, counting coup with caribou in Alaska, or chasing down poachers as an environmental police officer, the constant has been that indescribable sensation of feeling alive in the woods. “I only wish I could do it all again.”

Editor's Note: The NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum would like to thank all Veterans for their service on this Veterans Day. We continue to celebrate the hunting heritage so often shared by those who put on the uniform to serve our country.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]