by Jim Heffelfinger - Monday, December 6, 2021

As if we needed something else to worry about as we close out the second year of living with COVID-19. News reports are showing up regularly warning that a lot of whitetail deer have COVID and so we now need to take precautions in the woods. Deer are pretty good at socially distancing from us despite our best efforts to get closer. In the last two years, nationwide participation in hunting and other outdoor pursuits has increased tremendously as people found they can escape the confines of quarantine and mask mandates by fleeing to the woods and waters.

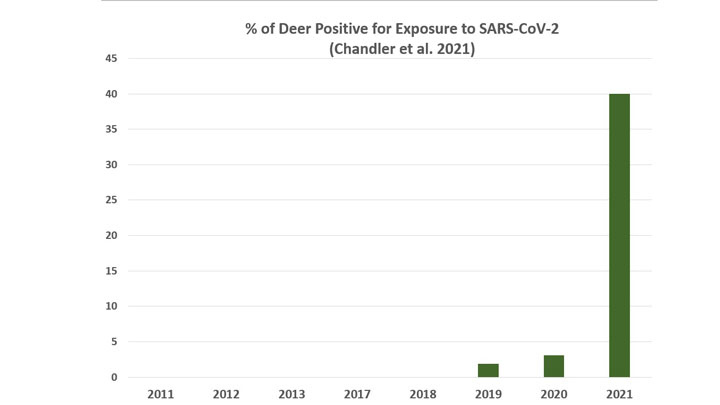

Sloppy reporting shows up in scary headlines about deer having COVID-19. Not true. A few studies of whitetail blood samples show evidence that a fairly high percentage (33-40 percent) of the deer tested have been exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19, but no deer has shown up with any clinical signs of being sick with COVID-19.

Researchers collected 385 deer samples from January-March 2021 in Illinois, Pennsylvania, Michigan and New York and found 40 percent of these samples had elevated antibody levels showing they had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. This surprising result forced researchers to investigate further to see if their test was just erroneously picking up a more common coronavirus that had naturally been in whitetails a long time. To test for this, they pulled 239 more blood samples out of the freezer that were collected from 2011-2021 in New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Michigan and Pennsylvania and tested them for exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Remarkably, they found that deer in these areas were not exposed to SARS-CoV-2 until the worldwide pandemic arrived in the central United States in January 2020. They detected SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in only one of the 143 samples collected before January 2020 (before widespread COVID-19 impacted the U.S. human population). Even though 40 percent of the overall 2021 samples were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, samples in half of the counties tested showed no exposure. It seems that there is a high degree of variability in exposure across the landscape, probably due to human population density and clustering.

It is extremely rare for wild animals we harvest to transmit any disease to humans. However, wildlife do carry some pathogens that can occasionally cause infections so it makes sense to follow a few simple guidelines from the CDC when handling wild animals:

About the Author

A wildlife biologist with degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Jim Heffelfinger has worked for state and federal wildlife agencies, universities and the private sector. He is the author of Deer of the Southwest and the author or coauthor of more than 200 magazine articles, 50 scientific papers, 20 book chapters and numerous outdoor TV scripts. Chairman of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Mule Deer Working Group representing 24 Western states and Canadian provinces, he also is the recipient of the Wallmo Award, presented to the leading mule deer biologist in North America, and was named the Mule Deer Foundation’s 2009 Professional of the Year. A member of the International Defensive Pistol Association and the U.S. Practical Shooting Association, Heffelfinger enjoys weekly competitions with his 1911. The opinions expressed here are his own and reflect his personal point of view.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]