by Jim Heffelfinger - Monday, March 22, 2021

Lead is a concern of bird enthusiasts because birds die from lead poisoning after consuming bullet fragments and shotgun pellets in unretrieved game animals and gut piles. Because of these mortalities, some organizations and individuals are mounting an aggressive campaign to warn hunters and their families about lead poisoning from eating venison shot with lead bullets. Suddenly some bird biologists are concerned about me and my family’s health. How much of this is an effort to reduce bird deaths and how much is a legitimate concern for the health of venison consumers?

There are many reasons hunters might choose nonlead bullets. Lead bullets do kill individual birds when they eat even small fragments, but this is not a population-level impact serious enough to require management action in the name of conservation. Reasons to choose nonlead bullets might be related to personal concerns for birds, superior bullet performance or concerns for the image of hunters in the general populace. This topic is too complex for one article, so I focus here only on the issue of lead bullets and human health.

Heavy Metal

Lead poisoning has been known in humans for at least 2,500 years. Some blamed it for the death of Beethoven and the fall of the Roman Empire. Research since then has revealed that high exposure to lead can cause impairments in brain function, heart problems, digestive issues, neurological ailments and developmental delays in children.

Lead is found in an inorganic metallic form that is the gray lead we normally think of, but also in an organic lead form used in various lead compounds (such as in cartridge primers). Most lead exposure in humans comes from organic lead compounds like lead additives in gasoline, lead paint and certain industrial compounds. Organic lead has properties that make it easily absorbed through the skin, mucus membranes and lung tissue. On the other hand, metallic lead used in bullets is harder for the body to absorb (rarely through the skin).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitors basic levels of toxicants in the U.S. population. The baseline blood lead levels in humans has decreased 86 percent since the 1970s as we removed the most widespread sources of lead exposure (gas, paint, etc.). The CDC considers a blood lead level of less than 10 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL) in adults to be an acceptable level. Despite this CDC threshold of 10mcg/dL, more recent research indicates a higher incidence of heart problems and childhood development issues when chronic levels were between 2 and 10mcg/dL. Children are more sensitive to lead because their digestive systems absorb lead at twice the rate of adults and because they are growing rapidly. Because of these concerns, in 2012 the CDC reduced the threshold for children to 5mcg/dL. Some say there is no safe level of lead, but despite ample research there is currently no evidence for concerns about lead levels below 2mcg/dL.

Blood lead levels are the standard for monitoring a person’s exposure but lead in the blood only reflects exposure in the last 30-60 days. More than 90 percent of the lead stored in adults is in bones and teeth. In bones, lead is not circulating in the body, but it can be mobilized as a person ages, especially if osteoporosis starts to mobilize calcium and lead into the bloodstream decades after being deposited. With females, lead stored in bone can be remobilized into the bloodstream during pregnancy and lactation or after menopause. Because of the greater susceptibility of a fetus to lead poisoning and long-term effects on child development, extra caution with lead is warranted in pregnant women (or those planning to become pregnant) and children under age 6.

Lead and Red Meat

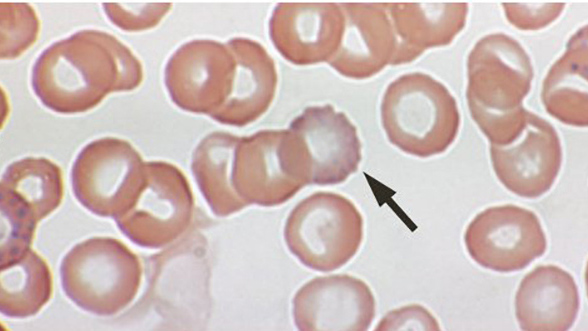

The soft nature of metallic lead not only allows for expansion of the bullet, but it allows the bullet to come apart and fragment when it hits meat and bone. It is not hard to find X-ray photos on the Internet showing the scatter of lead fragments in a carcass. Many pictures represent worst case scenarios from a high velocity, lightweight bullet that impacted solid bone. Nonetheless, lead bullets do fragment. Recent research shows even skeptical hunters that there is more lead in our venison (and farther from the wound channel) than we thought. With a well-placed shot in the rib cage, bullet fragments in the four quarters and backstraps should be minimal. Most of the contamination comes from the scraps of meat taken from the area near the wound channel, which typically end up in the “grind pile” for burger.

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources experimentally shot 80 carcasses and evaluated the presence of lead. High-velocity ballistic-tip bullets left an average of 141 fragments, an average of 11 inches from the wound channel. Soft-core and bonded bullets fragmented less and left “only” 80-86 fragments 9-11 inches from the wound channel. Some fragments were too small to see with anything but an X-ray image, but with this amount of fragmentation, you obviously want to keep all bloodshot meat out of your burger and sausage.

The whole topic of lead in venison was set afire in 2007 when a North Dakota dermatologist had 95 packages of venison burger X-rayed and found that 53 contained some trace of lead. This lit the fuse on an explosion of news articles and caused the removal of all donated venison from charitable food pantry shelves in at least four states. When it became known that the dermatologist was on the board of directors of a national bird organization, suspicions raged about his motives.

A study of 30 deer harvested with lead bullets in Wyoming and processed by 22 different meat processors found a similar number of average lead fragments per deer (136), and 32 percent of the burger packages had at least one metal fragment. Twenty percent had only one fragment, 7 percent had two fragments and 5 percent had three to eight fragments. Burger packages always have more lead fragments than steaks and roasts. The Minnesota Department of Agriculture tested 1,029 commercially ground burger packages and found fragments in 26 percent but only 2 percent of 209 packages containing whole cuts of meat. In a 2008 Wisconsin study, researchers collected 183 packages of venison burger from hunters’ freezers, food pantries and meat processors. They found 85 percent of commercially processed burger and 92 percent of hunter-ground packages were free of lead.

Lead Bullets and Human Health

There is no question lead is toxic to humans, but often people speak generally about medical complications from lead poisoning rather than specifically about metallic lead fragments from bullets. I’m not interested how Beethoven died, but I am interested in whether lead bullet fragments pose a health risk to my family. Metallic lead absorbs slowly in the human digestive tract, so what is the risk if I happen to get a burger with a lead fragment? It only takes 24-72 hours for a meal to pass completely through a person from table to toilet. Can a relatively insoluble lead fragment moving through your system that fast be a problem—especially if an average meal passes out of the stomach in four to five hours?

After the food pantry clearing in North Dakota, a blood lead level survey was conducted on 736 North Dakotans. It was widely reported that those who consumed wild game had twice the blood lead levels as those who did not. Media coverage of this was extensive, but even those who consumed game meat still had blood lead levels that averaged 1.27mcg/dL—about half the absolute lowest, most conservative safe level (2mcg/dL) and nearly identical to the national average (1.25mcg/dL). No participants in the study had levels above the CDC threshold (10mcg/dL). This sounds like an example of some people trying to make a big deal out of something that was not a health issue at all.

Another well-publicized study showed an Inuit community in Greenland had high blood lead levels after subsisting largely on shotgun-killed sea ducks. The more often people consumed sea ducks, the higher their blood lead level. Those eating ducks less than once per week had lead levels under the CDC threshold (10mcg/dL), but when consumption rate approached “daily,” lead levels exceeded the threshold (10-17mcg/dL). This study is often cited to illustrate the dangers of lead poisoning to hunters, but we need to keep things in perspective. Few hunters consume game shot with lead every day.

A study of venison consumption in Italy found hunters had blood lead levels of 3.4mcg/dL, twice the level of nonhunters (1.7mcg/dL), but again, even hunters had levels only one-third of the CDC-recommended threshold. A closer look shows there was no relationship between lead levels and those who ate game meat, so why was there a difference between hunters and nonhunters? Perhaps another source of lead confused the results. This was the case in Norway when those who consumed game meat had somewhat higher lead levels, but those who reloaded their own ammunition had 52 percent higher blood lead levels. This shows that those who consume game meat are also exposed to other sources of lead that may not be captured in the study design. In the famous North Dakota study, 35 percent of participants reported target shooting and 15 percent were reloaders.

The problem with other sources of lead confusing these results is familiar to me. If I were a survey subject, it would show that I hunt and eat venison twice per week year-round. It also would show I have had elevated blood lead levels (mcg/dL) of 18.4 (2013), 8.9 (2015), 16.7 (2018), 16.7 again (2019) and 8.5 (2020). This sounds like a clear case of elevated lead levels from bullet fragment ingestion—except my family has used nothing but solid copper bullets since 2009. My lead exposure comes from weekly pistol competitions and frequent reloading of ammunition with lead bullets. There are several sources of lead exposure related to my hobby and I have implemented more actions to reduce my exposure further, which is why my levels dropped to 8.5 in 2020. This had nothing to do with lead in venison. My example highlights the importance of not looking at lead levels with simplistic categories like “hunters vs. nonhunters” or “frequency of game meat consumption” without accounting for other potential sources of lead that hunters encounter.

There is no record of anyone ever getting sick from consuming lead bullet fragments unless it was daily. However, there is ample research that shows ingesting bullet fragments and bird shot can increase blood lead levels. Whether that is a health hazard depends on the amount of lead consumed, frequency of consumption, passage rate, age, sex and even differences between individuals. A temporary elevation of blood levels following occasional swallowing of a fragment will not result in a heart attack or loss of memory, but since lead is a toxin it is still good advice to minimize your intake. Studies show that those of us who butcher our own meat have less lead in our venison and that most of the problem is with burger and not whole cuts.

There are rare cases in medical literature of people retaining a piece of lead in their digestive tract for a long time, most commonly with shot pellets in the appendix. In these cases, blood lead levels can rise to high levels requiring medical attention. There are even cases of gunshot victims having elevated blood lead levels from the bullets that were not removed.

We certainly see cases of bird advocates exaggerating the dangers to hunters of lead bullet ingestion out of concern for bird deaths. You can’t blame them for being passionate about what they love, but we have to make personal ammunition decisions based on good science. There are legitimate reasons for hunters to think about their sources of lead exposure and do all they can to minimize their intake. Unless mandated by law (as in California), a switch to nonlead ammunition is up to the individual depending on their assessment of health risk and other reasons. If you are a female of child-bearing age or have kids around the table, your risk is different than a single person eating venison infrequently.

Those who consume high quantities of lead-killed venison should take precautions to lessen the risk and monitor their blood lead levels. However, all evidence indicates you would have to eat a lot of blood-shot burger frequently to maintain enough metallic lead in your digestive system for these fragments to be a dangerous source of lead poisoning. The CDC has never identified lead bullet fragments in venison as a human health issue, so let’s keep this conversation grounded in good science and avoid inflating the health issue if the concern is really for the birds.

About the Author

A wildlife biologist with degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Jim Heffelfinger has worked for state and federal wildlife agencies, universities and the private sector. He is the author of Deer of the Southwest and the author or coauthor of more than 200 magazine articles, 50 scientific papers, 20 book chapters and numerous outdoor TV scripts. Chairman of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Mule Deer Working Group representing 24 Western states and Canadian provinces, he also is the recipient of the Wallmo Award, presented to the leading mule deer biologist in North America, and was named the Mule Deer Foundation’s 2009 Professional of the Year. A member of the International Defensive Pistol Association and the U.S. Practical Shooting Association, Heffelfinger enjoys weekly competitions with his 1911. The opinions expressed here are his own and reflect his personal point of view.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.