by Mike Arnold - Thursday, October 6, 2022

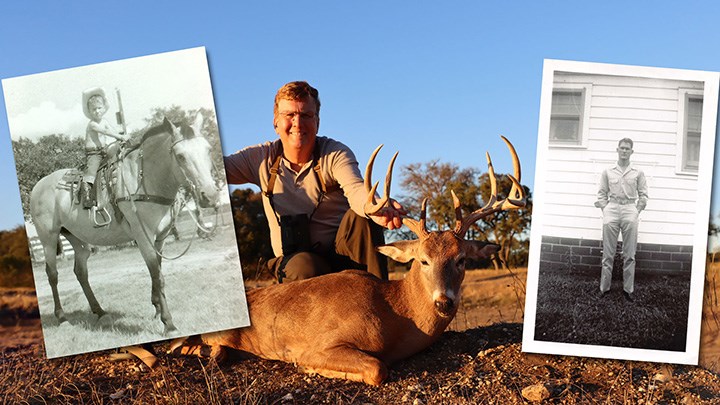

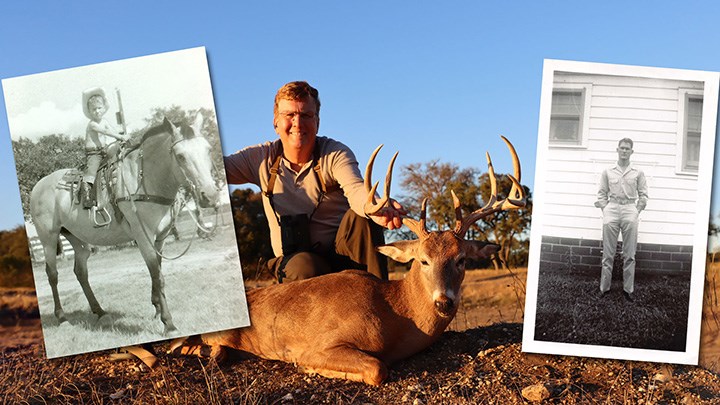

As my friend and guide, Dan, and I dragged the whitetail buck out from the cedar tree line, it brought back strong and wonderful memories about my first Texas Hill Country whitetail, taken not so far from this very spot—a doe that had been the realization of so many waking dreams, both my dad’s and my own, nearly 60 years ago.

I tried to lean closer to my dad as the Texas Hill Country began to take on that purple haze that Western authors love to use as a backdrop. I felt very small as I alternately attempted to peer over and then around my dad’s broad shoulders. As he felt me squirm, he made a soft hissing sound that meant “Sit Still!” There were two reasons that my squirming was inevitable: I was 5 years old and on my first whitetail deer hunt and I was freezing in the near dawn. It wasn’t that I lacked clothing as I was wearing long underwear with the button flap, a flannel shirt, heavy coat, corduroy pants, wool socks, gloves, hunting boots and a “Barney Fife” cap complete with ear flaps. It’s just that the clothes didn’t insulate my skinny body.

As I rested my face on the rough fabric of my dad’s coat, I thought back to my first night in the hunting club’s bunkhouse, nirvana for a 5-year-old. There was a hardwood floor covered with a fine coating of dust and deer mice droppings, the rustic kitchen/dining room area complete with picnic table and benches for seats, the numerous bunk beds that assured my finally getting a bottom bunk—and the outhouse. This made my year. It might seem odd that primitive toilet accommodations would be a highlight of my first whitetail expedition, but at five years old I was an unreconstructed cowboy, and cowboys used outhouses. Of course, I didn’t really appreciate the potential for an up close and personal encounter with the ever-lurking black widow spiders. Nowadays I am a typical soft adult, preferring the indoor, non-splintering version, but then I sat in resplendent glory as I contemplated the capture of my first whitetail trophy.

In the middle of my daydreaming, I felt my dad tense and then gently elbow me. This was our signal. There they were. What is it about whitetails that fascinate and excite hunters and non-hunters alike? Whatever it was, it had me in its grip as I watched the two does pick their way down the trail that ran not more than 10 yards in front of our blind. My dad lifted the .243 Winchester bolt-action rifle from his lap and laid it across his right shoulder. I slowly drew my knees under my body, raised myself until I was shouldering the rifle and peering through the scope.

By the time I got the crosshairs on the lead doe, she was already directly in front of us. Unfortunately, the short distance and minimal light conspired to make the doe into an indistinct blob. Try as I might, I could not tell her shoulder from her tail. Finally, after what seemed like an hour, I aimed at the forward portion of the doe and jerked the trigger. It was immediately apparent that I had not squeezed the trigger because a divot of grass flew up directly from under the doe’s belly. My heart sank as I looked up in time to see the white “flags” disappear into the brush near the trail’s edge.

My dad slowly set aside the gun, pulled out a cigarette, lit it and asked me what I thought had gone wrong. I explained that I couldn’t tell head from tail of the doe in my scope. He nodded and said he understood that, but had there been anything else? I hesitated and said, “I guess I yanked the trigger because I was excited to take my first shot at a deer.” I was surprised by his response. I sort of expected him to be angry with me over the blown opportunity. Instead, he told me about the several times he had gotten buck fever, even when shooting at does. He said that this could happen again if I kept hunting. Learning to enjoy and control the excitement was one of the pleasures of pursuing big game. I said I would try and remember for next time. Though at that moment, I wondered if there would be a next time.

The last day of the hunt began just like the previous six. Brittle-dry, frost-covered grass crunched under my boots as I followed my dad to a new area and a new ground blind. Including the first doe I had missed, I now had cleanly missed four deer. This morning’s plan was significantly different from all the previous ones in one crucial aspect. The other hunters in the camp were keenly aware of the youngest member’s “deerlessness.” In an example of what I see as the ultimate in hunter kindness, they had banded together and planned a drive. I would be the only person allowed to take a shot at driven deer. I now realize that these were men and women who knew what a first deer would mean to a young boy—that it would mean more and more to him as he grew older. That it, and other fulfilled dreams, would furnish the fire for pursuing more difficult achievements. This boy’s own child one day would challenge him to explain why he pursued seemingly unreachable goals. These men were helping him construct his answer: “Because I have seen other goals achieved that I didn’t think could be reached.”

My dad and I sat in our blind and watched the country turn gray, blue, purple, pink and then a different color of gray. We watched the hill opposite from us and hoped for movement. The sun had been up an hour when the first grayish-tan form sneaked through the brush in front of us. It was a doe, followed by two more does and a yearling. They weren’t running but moving steadily down the distant slope. My dad readied the gun, and I gripped it as I knelt behind him once again. When we first spotted them, the deer were 500 yards away. My dad’s instructions, given as we sat in the predawn chill, were to wait until the animals moved over the rise immediately in the foreground. This would place them at a maximum of 75 yards. We had misjudged where the deer might come out as they appeared in a gap a mere 40 yards away, first the yearling, then an almost fully-grown doe and finally the mature doe. In my mind’s eye, I still see her broad, black nose, her ears moving while she moved her neck like a periscope and looked straight at us.

I froze until she looked away and then slipped my cheek onto the comb of the stock. The crosshairs settled behind her shoulder, for once remaining steady. The trigger crept slightly, and the gun cracked. There was a moment when I saw the doe rear and then start a crouching run so low that it appeared she was on her knees. I watched and started to wonder if I had missed again before she stumbled and went down. My dad grabbed me and pounded my back. I jogged toward the doe, hardly believing what had happened. I knelt and placed my finger on the small hole in her side and then stroked her skin. I was thus engaged when the other hunters arrived. They gathered around as my dad bent over to field dress the deer. After he made the initial incision, he placed his knife on the doe and stood up, blood covering his right hand. With all the hunters smiling and quietly cheering, he spread the blood from his hand onto both of my cheeks. As he did this, he said to me, “You’re now a deer hunter, son.” His eyes were shining, and he gave me one of his infrequent smiles. This ritual, now considered bloodthirsty by our comfortably sanitized culture, marked my entrance into more than just deer hunting. It also marked my joining a society of men and women who truly know the wonder of the taking of wild animals—not merely killing, but hunting. No animal dies in vain if it brings such moments to fruition.

About the Author: Outdoor writer and hunter Mike Arnold has had more than 150 articles published in magazines including Sports Afield, African Hunting Gazette, Hunter’s Horn and Safari. Combining his love of hunting and conservation with his passion for science, he serves as a distinguished research professor of genetics at the University of Georgia and has written numerous research articles and four books on topics including conservation biology. His new book, “Bringing Back the Lions: International Hunters, Local Tribespeople and the Miraculous Rescue of a Doomed Ecosystem in Mozambique,” shares the modern-day wildlife conservation story of Mozambique’s Coutada 11. It tracks the country’s progress from its poached-out days as a source of bush meat for starving villagers to the arrival of hunting outfitter Mark Haldane and his partners in the 1990s, who restored a unique ecosystem once decimated by civil war.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.