by Jim Heffelfinger - Monday, August 7, 2023

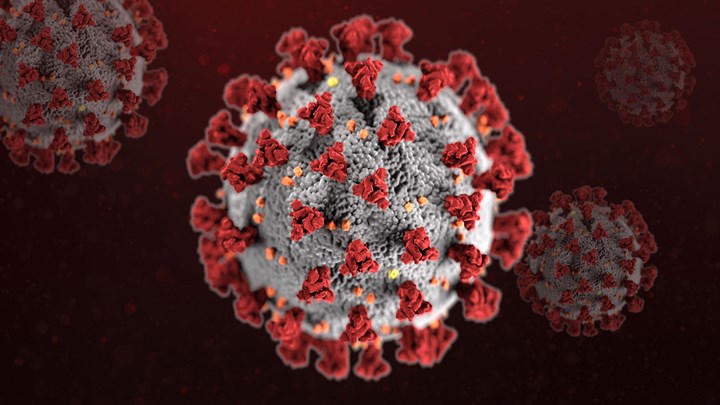

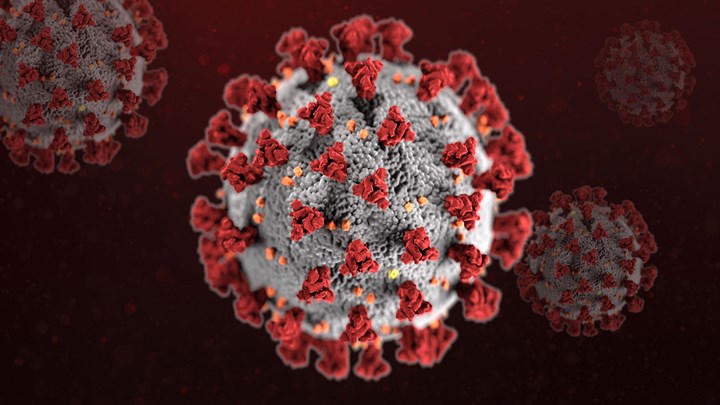

We may all be a bit tired of hearing about SARS-CoV-2 infection and spread, but wildlife disease researchers are not taking their eyes off that spikey little ball. As hunters, we need to learn more in the face of mounting evidence that whitetail deer are a reservoir for the virus, where it can persist and evolve to potentially spill back into the human population.

Since its first appearance on the world stage in December 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19 has continued to evolve in an attempt to outsmart the human immune system. As it spread from human to human, it rapidly adapted and produced numerous SARS-CoV-2 genetic variants that we have given fraternity like names such as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron.

Unfortunately, humans are not the only species being infected by the virus. Researchers soon found that deer share the same primary SARS-CoV-2 receptor (ACE2) with humans, which means they are susceptible to infection from this virus. In addition to deer, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been documented in 31 animal species including mink, rats, otters, ferrets, hamsters, gorillas, cats, dogs, lions and tigers.

To learn more and get a handle on this situation, Congress provided the U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) $300 million through the 2021 American Rescue Plan to look specifically for SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife species. The USDA surveillance effort is producing a growing body of information to help us understand if deer play a role in the spread of this virus. Preliminary results showed that eastern white-tailed deer have a surprisingly high rate of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. For example, 40 percent of 385 whitetail samples collected from January through March 2021 in Illinois, Pennsylvania, Michigan and New York contained antibodies showing they were exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Other testing in the East showed whitetails were exposed to the virus in Iowa (33 percent), Ohio (36 percent), Staten Island, N.Y. (15 percent), Quebec (5.6 percent), Ontario (6 percent) and Texas (0-94 percent among captive facilities).

Interestingly, researchers in several of these studies were able to show that the viral variants circulating in the human population at the time were the same that deer were carrying.

SARS-CoV-2 variants in the deer population closely follow the most recent flareups in the human population. In other words, the Delta variant was found in deer just months after it peaked in humans. When Omicron reared its ugly head in humans, wild deer soon started testing positive for that variant. Variants were also detected in the deer population a long time after they had swept through the human population and in some cases very rare variants were still being circulated deer-to-deer in the woods, and the virus was changing slightly as it did.

It is clear that deer are being exposed to the virus from humans and then spreading it amongst themselves. Deer typically do a good job of social-distancing from humans, so it is not clear how deer might be getting infected, but all evidence points to contact with humans or human waste. Humans and white-tailed deer interact much more in the eastern United States because deer have adapted to our presence and wander through back yards to eat our shrubs and gardens.

However, deer are not getting the Covid-19 disease as is often erroneously reported. Deer are being exposed to the virus that causes Covid-19, but deer are not getting sick like humans are. If deer are not getting Covid-19, then it begs the question: “So what?” The answer is “spillback.” Health experts worry about SARS-CoV-2 spreading throughout deer populations, completely separate from humans, and mutating slowly as it is passes from deer to deer. When that happens—and it is happening—the virus adapts independently of the human immune system and results in variants that humans have not had a chance to adapt to along the way. This creates a potentially dangerous situation if it then spills back into the human population. As it turns out, there is a reason to worry because it has happened in a couple cases involving mink, deer and maybe domestic cats.

Mink are also susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Surveillance in the Netherlands documented the virus circulating in 16 mink farms and mutating as it spread into a slightly different version. Intensive testing at the time detected the mutated mink version of the virus in 68 percent of the mink farm workers, most of whom developed symptoms of Covid-19. Luckily, there was nothing unusual about their symptoms.

In July 2023, researchers published the current results of the ongoing nationwide surveillance program for SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife. They collected 8,830 samples from wild white-tailed deer across 26 states between November 2021 and April 2022. From those samples, they were able to identify 391 unique genetic versions of the virus grouped into 34 lineages including the Alpha, Gamma, Delta and Omicron variants. They were able to trace these different versions of the virus in whitetail deer to determine where they originated. The research team documented at least 109 separate times SARS-CoV-2 spilled over from humans to deer and 39 cases of deer transmitting it to other deer.

Researchers also compared the genetic sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 viruses they collected from deer to a published database that contains all genetic sequences of this virus ever sampled in humans. They found three cases where a viral variant clearly evolved differently in the deer herd and then spilled back into the human population and infected three people in two states: North Carolina and Maine.

However, this is not the first case of the virus mutating into a very different lineage and then reinfecting a human. In 2020, researchers identified a very different version of the Omicron variant circulating among 6 percent of the whitetails sampled in southwestern Ontario, Canada. Genetic evidence indicates it was circulating in deer separate from humans for quite a while before this altered version of Omicron was detected in a human.

By contrast, Europe has not seen the same level of SARS-CoV-2 infection in its deer. Previous surveillance of more than 400 roe deer, red deer and fallow deer in Europe failed to find any positive test results. But a fallow deer recently tested positive in a semi-wild, free-ranging population in the largest urban park in Europe, the. This park has 10 million visitors each year, and park visitors sometimes hand-feed the deer.

None of this is cause for alarm if you find yourself close to deer occasionally—such as in the hunting woods. Considering such a high incidence of exposure in whitetail deer, it appears to be very rare for humans to be infected directly from deer. Also, none of the cases of spillback to humans from deer or mink have resulted in a more serious illness than normal in the human recipients. Despite the recent evidence of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from deer to humans, experts are not concerned about deer perpetuating a Covid-19 pandemic. Dr. Anne Justice-Allen, chair of the Wildlife Health Committee for the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, said: “There is no evidence that deer are an important source of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans, and all evidence indicates the probability of getting COVID-19 from an animal is very low.”

There is also no evidence that people can get COVID-19 by preparing or eating meat from an animal infected with SARS-CoV-2. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, completely inactivating this virus only takes three minutes at 160 degrees Fahrenheit, five minutes above 149 degrees Fahrenheit and 20 minutes above 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Even deer with an active infection only shed the virus in the environment for three to five days after being infected, so just because some percentage of the deer population has antibodies from a past exposure doesn't mean we should quarantine ourselves during deer season.

About the Author

A wildlife biologist with degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Jim Heffelfinger has worked for state and federal wildlife agencies and universities and in the private sector. He is the author of Deer of the Southwest and the author or coauthor of more than 200 magazine articles, 50 scientific papers, 20 book chapters and numerous outdoor TV scripts. Chairman of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Mule Deer Working Group, representing 24 Western states and Canadian provinces, he also is the recipient of the Wallmo Award, presented to the leading mule deer biologist in North America, and was named the Mule Deer Foundation’s 2009 Professional of the Year. A member of the International Defensive Pistol Association and the U.S. Practical Shooting Association, Heffelfinger enjoys weekly competitions with his 1911. The opinions expressed here are his own and reflect his personal point of view.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.