by Mike Arnold - Monday, August 4, 2025

Passing the sandbar, the hippos and crocodiles looked like so many enormous boulders and logs. Interspersed with one another, it seemed that a détente existed between these ofttimes enemies as they lounged in the sun. Though finding them interesting, my focus was not on the hippos, but rather the reptiles lying around on the warm sand. Some of the huge lizards were, in the words of my Zambeze Delta Safaris professional hunter, Dylan Holmes, “shooters.” Unfortunately, they rested in broad daylight within the reserve boundaries and thus were not only huge, but non-huntable. We were on our last day of our hunt for a crocodile, and we were running out of daylight and time. We’d spent the two previous days in unsuccessful attempts at baiting a large crocodile using the carcass from my hyena taken on the first night, and the head of a blue wildebeest taken for camp food. No shot opportunities came when watching the baits, but it was stunning watching several crocodiles push, shove and thrash the water while tearing chunks of meat from the carcasses.

As Dylan motored into the final cove before the boat ramp from which we began our trek on Mozambique’s Lake Massinger, he raised his binocular to his eyes and stated, “There is a croc on that shore.” Glancing up, my binocular-rangefinder remained on my chest as I took in a sharp breath followed by, “Holy crap, he is huge!” Dylan’s calm response: “Yes, he is, and there is no way we will spot-and-stalk him. The only option is a shot from the boat.” Dylan and I discussed earlier the difficulty of a shot at a crocodile from the boat, given the unsteady nature of the rest, at least compared to a land-based support.

Dylan and my tracker, Albiñio, slowly and quietly paddled the boat to about 100 yards from the sleeping crocodile. Fortunately, it was a gently rocking boat as I took aim at a target the size of an orange, despite the monster lizard’s body size. My happiness in collecting the 14-foot animal existed because of several facts: He was a huge and mature crocodile; he was a known maneater, killing a farmer some three weeks before; and the meat from this 1,500-pound animal meant meals on the tables of many local families for many months. After taking off the skin and fat that likely weighed some 300 and 200 pounds, respectively, there remained an estimated 900 pounds of lean meat. Much of that would end up as biltong, with some of the fresh meat broiled over coals when brought into the local villages that night.

One of my goals on every hunting trip rests with exploring the many community outreach opportunities resulting from the passion of sportsmen and women. On this safari, my wife, Frances, and I were back in Mozambique, this time in the district of Massingir near Kruger National Park in South Africa and Limpopo National Park in Mozambique. As mentioned, the crocodile hunt afforded the chance to provide much-needed and cherished meat protein for local families, in this case the farmer and fisher communities on Lake Massingir. However, that was not the only significant example of community outreach through hunting we experienced while on this safari.

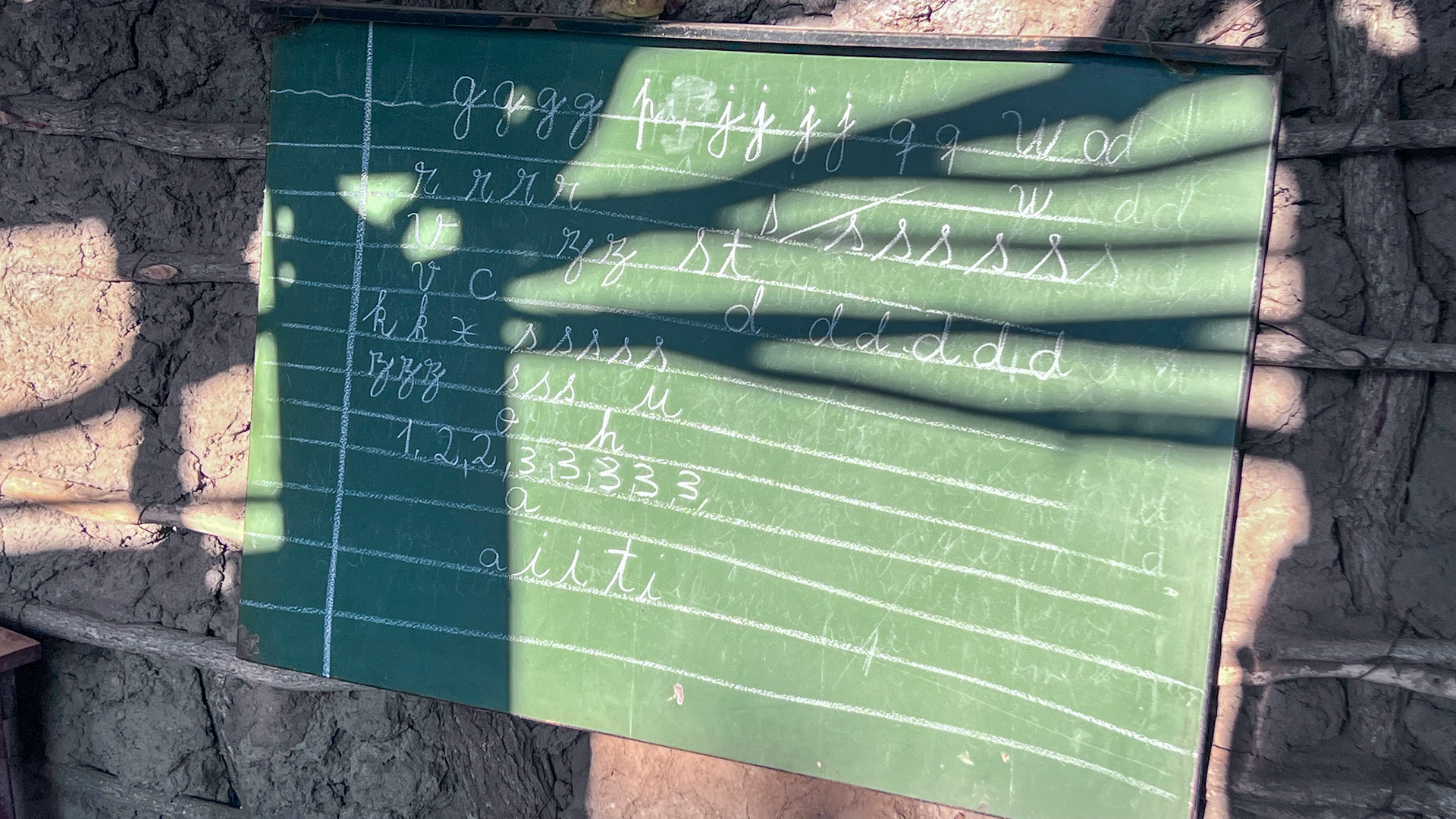

The day after achieving my dream of taking a huge crocodile, and in this case ridding the local inhabitants of a dangerous scourge, Dylan drove Frances and me to see some of the community projects underwritten by Zambeze Delta Safaris in partnership with Massingir Safaris. Three local villages fell under the auspices of the charitable work by these two businesses. In the village of Panguene, an educational uplift undertaking involved replacing a small, one-room schoolhouse constructed from mud and sticks with a large, four-classroom concrete school building.

Walking around the outside, and the interior of the tiny, original school building made me realize that it must leak during rain, and with only stray sunbeams penetrating as a light source, the visibility of teachers and the blackboard must be very limited. With a proposed completion date within a few months after our visit, the local children would soon experience something wonderful, and yet impossible without the tremendous financial input and physical outlay by the two outfitters, their staff and their clients. As we loaded back into the Land Cruiser, I commented to Dylan that there would be hundreds, if not thousands, of young lives impacted positively and given previously unimaginable prospects for advancement in life. (If you would like to hear the author discuss this and the other outreach projects, check out this video by clicking here.

Our next project for review was one that scratched a major itch for local children as well, these belonging to the village of Deca de Vitoria. The work involved the construction, from clearing to grading, to setting the goalposts, to painting said posts for a soccer (a.k.a football) field (known as a “pitch” in most of the world, including Mozambique). The photos don’t do justice to the amount of work involved in clearing a brushy area large enough for a full-scale soccer field – one without rocks, sticks, etc. that plagued many rural fields we passed while on our hunting forays. The rural setting for this project is (ironically) apparent in the photograph of the preparation of the goalposts. The large herd of cattle in the background belonged to farmers—and the grateful parents of the Deca de Vitoria youngsters who will play many matches on this pitch, for many years to come.

That evening as we sat with our sundowners near the firepit at the Massingir camp, Frances and I discussed again the graciousness of hunters and their outfitters. No one requires the types of investments we ourselves made by giving hundreds of pounds of meat to local people so that they avoid hunger. However, to quote another of our outfitter friends, this one working in South Africa, “Outreach projects are not something we must do from compulsion, it is something we know we should do from kindness and compassion.” This is the mantra Frances and I see and hear from hunters throughout the world. That is why we are proud members of this community.

About the Author

Mike Arnold is professor and head of the Department of Genetics at the University of Georgia and author of the 2022 book Bringing Back the Lions: International Hunters, Local Tribespeople, and the Miraculous Rescue of a Doomed Ecosystem in Mozambique. The book is available for purchase at bringingbackthelions.com. You can find a description of his travels, talks and articles at mikearnoldoutdoors.com.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.