by Ron Spomer - Sunday, January 6, 2019

According to some noisy people on social media, there is nothing sporting about “sport hunting.” Harassing and killing animals for some kind of cheap thrill is sick, they say.

Well, yes. But killing animals for cheap thrills is NOT sport hunting. It’s vandalism. What we have here is a failure to communicate. What we need is a definition of terms. So let’s set the record straight by clearly defining “sport hunting.”

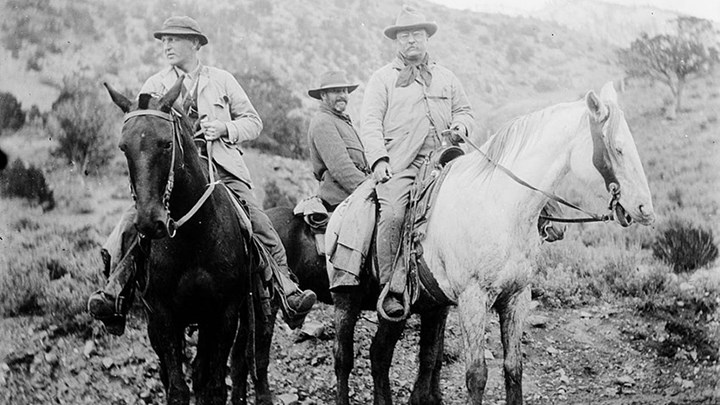

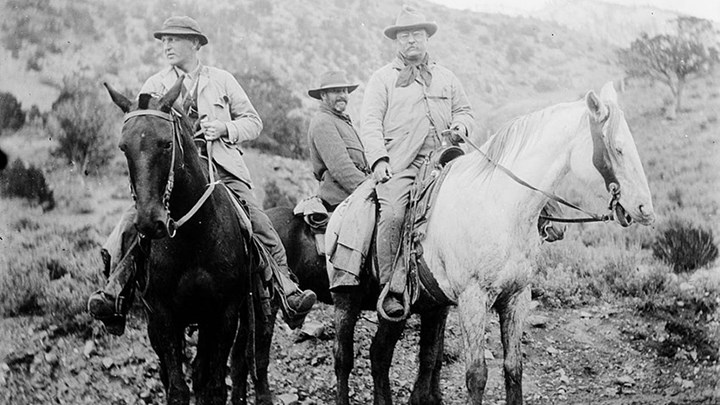

“Sport hunting” was coined by early conservation hunters (think Theodore Roosevelt) to differentiate what they did from what "market hunters," who were commercial hunters of wild game, or poachers did. Prior to the late 1800s citizens in the USA were free to shoot, trap, poison or capture just about anything wild. Deer, walnut trees, lobsters, bears, ginseng root, robins, walnut trees, bison, canvasbacks… As long as no one owned it, it was free for the taking. The result was a classic tragedy of the commons. Because everyone had equal right to wild resources but no one had responsibility for managing them, serious depletion resulted. It was a “me first” ethos. Get yours before it’s gone.

During this free-for-all era, some species like Labrador ducks and passenger pigeons were exterminated. Turkeys, pronghorns, herons, egrets, several shorebird species, bison and even whitetail deer were dwindling to scarcity. Entire biotic communities like forests and prairies were being cut, burned and plowed into oblivion.

Recognizing the inevitable bankruptcy of such abuse, concerned hunters and outdoor magazines like Forest and Stream began advocating for restraint, for harvest limits, for responsible management of wild resources so they could replenish annually, maintain healthy numbers and balance, and sustain a healthy ecosystem indefinitely. And therein lies the basis for calling it sport hunting.

“Sport hunters” created and advanced a sporting code of hunter ethics, essentially self-imposed limitations on where, when, what, how and how much game could be taken. No deer hunting at night with spotlights. No hunting during the spring and summer rearing seasons. No shooting does, fawns, cubs or hens. No poison-tipped arrows, fully automatic firearms or punt guns. No shooting from motorized vehicles. No wanton waste of meat. No more than three pheasants per day, one deer per season, one moose every 10 years or one bighorn sheep per lifetime.

Additionally sport hunters taxed themselves through license and tag fees, using the funds to hire biologists and game wardens to manage and maintain wildlife abundance. It worked and still works. Game species on the brink of extinction in 1900 are again abundant. So abundant that for a century they’ve been thriving despite (or because of) annual hunting seasons and harvests—even with ongoing habitat destruction for highways, cities, suburbs, reservoirs, golf courses, vineyards and crop fields. Not only have game species bounced back, but they seem to have improved in genetic quality or at least expression. New world-record antlers and horns for nearly every recognized big game species and subspecies in North America have been collected in the past 40 years. Many of those have come in the last 20 years.

So there we have it. Sport hunting is governed by rules, rules and more rules. By limitations and more limitations. What does that remind you of? A sport, perhaps? Like, no leaving the line of scrimmage before the ball is hiked? No blocking from the back? No head-butting?

Rules and limits are inherent in sports. It’s what differentiates games from tribal warfare, from all-out, no-holds-barred competition and exploitation. Instead of throwing rocks at our neighbor’s heads, we throw them at a target. Instead of choking our rivals to death, we pin them to the mat for three seconds. Instead of killing wildlife indiscriminately, sport hunters severely restrict and limit their harvest.

And that is why sport hunting is called sport hunting. Not because it’s a frivolous, meaningless game, but because it’s a vital, essential life-and-death interaction with Nature that sport hunters intend to maintain, sustain and perpetuate.

■ ■ ■

About the Author

Award-winning outdoor writer and contributor Ron Spomer says hunting is everyone's way of connecting with true freedom—the freedom to interact with Earth as naturally as does a wolf, falcon or chickadee. During more than 50 seasons afield, Spomer has decades of hunting experience and writes regularly for multiple outdoor publications, including NRA Publications, sharing his vast knowledge on guns, ammo, optics and gear. For more information, including his top hunting tips and tactics, visit his website, Ron Spomer Outdoors.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.