by Steve Scott - Friday, April 26, 2019

We have seen it before: An American hunter travels abroad, harvests a rare species of wildlife, then mainstream and social media go ballistic. But this time, a modern-day miracle occurred: Logic prevailed.

In a strange and wonderful twist to the all-too-familiar portrayal of hunter-as-villain, many media outlets are giving at least equal time to the conservation benefits of sustainable-use hunting, in this case in Pakistan.

So far this hunting season, three Astor markhor goats have been harvested by Americans in the Gilgit region of Pakistan. Most recently, a hunter named Bryan Harlan paid a record $110,000 for the permit, one of four which will be sold this year. The record price Harlan paid to hunt markhor was what garnered the media attention, but importantly, some media outlets have taken notice as to where the money from the hunting permit goes. In this case, 20 percent went to the Pakistan wildlife department and 80 percent directly to the local community. Of course, this kind of revenue sharing from hunting is nothing new. The CAMPFIRE program in Zimbabwe has been benefiting local communities for decades. But in Pakistan, with the fate of a threatened species on the line, the tangible benefits of tourist hunting have proven to be the catalyst for the recent improvement in markhor numbers and, at least, some media outlets are reporting on it.

Hunting to conserve wildlife is a difficult concept to understand, especially if all you know about the subject is what is portrayed in most of today’s news outlets. In Pakistan, however, the causal relationship between hunting and increasing wildlife populations is so clear and obvious that many media outlets are giving the “conservation aspect” of the story at least equal time with the “moral outrage” from usual suspects in the animal rights world.

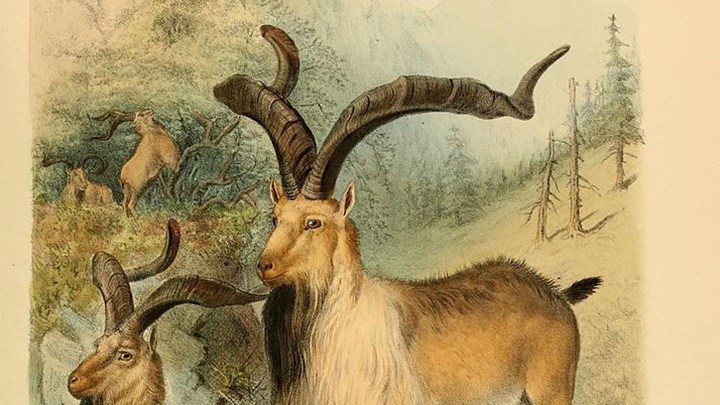

Putting Value on the Animal Pays OffThe markhor population in the Himalayas has been in a long decline due to a combination of factors including deforestation, local meat poaching, military activities, competition from domestic livestock and illegal trophy hunting by politicians and local authorities, all of which combined to reduce the world’s population of markhors to about 2,500. To save the species, Pakistan officials knew they had to try something different.

First, the government banned all local hunting of markhor but allowed foreign hunters who could afford the expensive tag a small quota of male goats in “community conservation areas,” which would receive 80 percent of the tag revenue. Then the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stepped in and downlisted the markhor from endangered to threatened, paving the way for American hunters to legally bring their trophies home. These actions put the markhor back in play in the international hunting market, and sportsmen—mostly from the United States—began hunting markhor in Pakistan. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear this was the turning point in the markhor’s impressive recovery.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) downlisted the markhor from “threatened” to "near threatened” on its Red List of Threatened Species, with the population of these spiral-horned goats increasing from approximately 2,500 in 2010 to more than 5,700 goats today. And though the anti-hunting, animal rights extremists will deny it—and CNN will not cover it—it was the revenue from hunting that made the comeback of the markhor possible.

In today’s 7.5 billion-person world, wildlife must pay its way in order to survive. Before paying tourist hunters were allowed in Pakistan, the markhor population was in deep decline. It had no value to the locals other than the few days’ worth of meat that a poached goat would provide. But when the local leaders realized those same animals would net their community more than $300,000 from tourist hunting each year, poaching stopped dead in its tracks. Rather than being seen as competition for limited grazing resources, the markhor now represents a new medical clinic, schools, sanitation projects and other improvements for local people—all because of the revenue generated by hunters, who paid to harvest four male markhor amongst the approximately 1,200 in the region. In fact, the monetary incentive hunting imbued to the markhor worked so well it had unintended consequences as some wolves and other predator species were trapped and killed by locals to prevent them from preying upon the markhor.

As hunters, we must appreciate our victories when we can. We will never win with some, no matter how convincing the evidence. But when outlets like NPR, The Washington Post and others report on the conservation benefits of sustainable-use offtake, we should count it as a victory for hunters. Considering the source, it is a rare victory indeed.

About the Author: Steve Scott is a reformed attorney, long-time university instructor and producer and host of "Safari Hunter’s Journal" and "Outdoor Guide" television series on air and online. For more information, visit SteveScott.TV.

Follow the NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.