by Joe Coogan - Tuesday, July 16, 2019

“The value of a trophy is computed directly in terms of personal investment in its acquisition.”

—Robert Ruark, Horn of the Hunter, 1952

In recent years, hunters have shied away from the label “trophy” hunter because of the negative connotation put forth by anti-hunters, but truth is, anyone who hunts is a trophy hunter to a greater or lesser degree. The term “trophy hunter” suggests that the “trophy,” such as horns, antlers, tusks, skin, etc., is the sole reason for the hunt. However, the vast majority of us who hunt do so more for the challenge of an enriching experience, surrounded by the beauty of nature and in the company of good friends. For most, the “trophy” serves as a respectful appreciation of the animal taken and an acknowledgment of a memorable hunt.

Avoiding or denying the “trophy hunter” label does not prevent many of us from dreaming of taking a “record-class” or “trophy” animal—one that’s large enough to meet or surpass a minimum-size requirement as stipulated in record books published by Boone and Crockett, Pope and Young, Rowland Ward or Safari Club International. It is important to emphasize that while “trophy” hunters are focused on taking a larger representative of the species, they still use the meat from the animal, whether to feed themselves and their families or local communities.

The reality is that animals large enough to qualify for inclusion in the record books are larger than average and being the largest specimens of their kind, they are generally older animals that have lived well beyond maturity. Therefore, they are much fewer in number and because they have survived by successfully eluding danger and suspected threats, they are all the more challenging to find and bring to bag.

The purpose of recording an animal’s measurements was never to determine the success or failure of a hunt, but rather to record listings that would provide historical yardsticks by which horns, antlers, tusks and skulls that are attained through legal, regulated sport hunting are measured and judged for posterity. The lists not only tell a story about a given species’ dimensions, but also record when, where and by whom the animal was taken. This provides a geographic and historical perspective that becomes relevant when the details are viewed as a whole. The listings reflect areas that produce the largest specimens, and cyclical ups and downs become evident on a timeline.

Listing the names of hunters is where the bugaboos and shenanigans begin. Obsessions with “making the book” has caused dishonesty, controversy and unethical behavior by those who probably are hunting for the wrong reasons.

Those who are fixated on an animal’s horn, antler or body size to the exclusion of all else, including the experience and effort of the hunt, are the ones who arrive in a hunting camp clutching a record book in one hand and a tape measure in the other. They approach their hunt with lofty aspirations of bagging “book” animals and judging the success of their hunt in fractions of an inch. I’ve even seen them fail to congratulate a companion’s good fortune when a “good” animal that’s not their own is brought into camp.

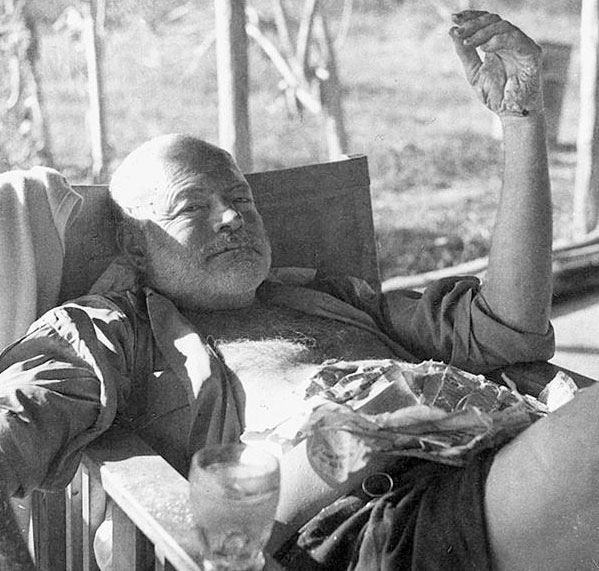

Ernest Hemingway suffered from a kind of jealousy that might be called “trophy envy,” even admitting so in his book Green Hills of Africa. When his hunting companion and good friend Karl (Charles Thompson) collected a kudu that was several inches larger than his own kudu, Hemingway’s aggressively competitive spirit reared its ugly head, causing him to privately bemoan his friend’s success to his wife, Pauline, who harbored no sympathy for his “silly issues.”

It’s important to keep record-class sizes in proper perspective and recognize that the animal you’re likely to take on most hunts will be of average size. The law of averages dictates that most of the game taken on hunts in any given area will fall within an average size range and, therefore, most sport-hunted game will never qualify for inclusion in a record book. What is important, regardless of size, is that only mature animals be taken.

Should you be lucky enough to take an animal that qualifies for inclusion in a record book, then count your blessings because you've earned a place among a very small number of hunters. But never diminish the value of those mature, typical animals that fit into an average size range. Stories of some of the largest trophies ever taken indicate that many came to bag unexpectedly. As an older, experienced hunter once observed, “The biggest trophies get taken when an animal makes a mistake, and a hunter just happens to be there."

But, beyond the increments of a tape measure the most significant aspect of hunting is the experience of the hunt itself—the highs, the lows, the funny happenings, the difficulties, and when it does happen, the exhilaration of taking a mature animal you’ve worked hard for, no matter what the horn or body size measures.

Ultimately, trophy value rests in the mind of the beholder and has little to do with size and record books. Writer and frequent safarist Robert Ruark knew his way around words and African game, and in his popular book, Horn of the Hunter, he described his feelings about taking a very large buffalo that came too easily, by his way of thinking. “…this was a big buff and a handsome buff, but the littler one, the uglier one, is the one I got hanging on the wall. You are not always successful at hunting, but there is satisfaction in the effort you put into the hunt—satisfaction surpassing the easy conquest, the freakish accident that provides reward without work.”

Ruark’s professional hunter, the legendary Harry Selby, added his feelings about hunting Africa’s biggest game while they were on safari in Kenya. “You are not shooting an elephant,” Selby said. “You are shooting the symbol of his tusks. You are not shooting to kill. You are shooting to make immortal the thing you shoot. To kill just anything is a sin. To kill something that will be dead soon, but is so fine as to give you pleasure for years, is wonderful.”

"...You are not shooting to kill. You are shooting to make immortal the thing you shoot. To kill just anything is a sin. To kill something that will be dead soon, but is so fine as to give you pleasure for years, is wonderful.”—Harry Selby, Professional Hunter

Over the course of more than 50 years on safari, Harry Selby experienced many exciting times and events that he enjoyed recollecting and recounting around a campfire. His memories of a lifetime spent afield were the safari trophies that he savored the most.

When the hunt results in a “trophy,” which is not necessarily a set of antlers or horns, but which might be meat, feathers, fur, spurs, claws, skin, hair, scales, teeth, tusks or even a photo, those are the objects that enable us to not only remember, but also commemorate the hunt. All trophies, no matter what in nature, have two things in common: They acknowledge the animal and they bring back the memory of the hunting experience. In reality, the best “trophy” of all is the memory of the experience and of those you were with during the hunt.

About the Author: Joe Coogan spent his younger years living in Kenya, East Africa, with his family during the 1960s and 1970s. As an avid hunter, shooter and outdoorsman, his early Kenya experience prepared him for safari work for many years as a professional hunter (PH) in Botswana and Tanzania. In 1972, Coogan earned a degree in journalism from the University of South Florida, returning to Africa to work for the renowned safari firm Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safaris. He joined its Botswana operation under the leadership of the renowned Harry Selby and earned his PH license under Selby’s guidance. Coogan conducted hunting safaris in Botswana for KDS Safaris and Safari South for the next 20 years. In 1991, he joined the editorial staff of Petersen’s Hunting, relocating to Los Angeles. In 2001, following a three-year stint in Arkansas managing a wildlife project, he returned to Africa when he joined Arusha-based Tanzania Game Tracker Safaris (TGTS), conducting hunting and photographic safaris in Tanzania for the next five years. In 2006, Coogan joined Benelli USA as its brand marketing manager, hosting its popular "Benelli On Assignment" outdoor TV show for six years. Today, he is a field editor for the NRA’s American Hunter and travels between his home state of Florida and Botswana, arranging and conducting safaris throughout Africa.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]