by Joe Coogan - Wednesday, July 3, 2019

Following in the wake of Botswana’s decision to lift a hunting ban implemented in 2014 by former president Ian Khama, a groundswell of emotional outbursts has muddied the waters of reason. The rush to chime in with ill-informed, politicized opinion on the matter has almost drowned out the knowledgeable voices of reason trying to explain the rationale behind Botswana’s decision. The simple matter of fact is that unless you’ve been to Africa and traveled beyond the beaten paths and comfortable accommodations found in the continent’s national parks, it is difficult to understand the reasons why Africa’s precious wildlife is in such peril.

Seeing firsthand how rural Africans live and what they must endure to survive from day to day puts a sharp focus on the conflict, competition and threat that wildlife presents to their lives. Imagine how the United States, or any other densely populated, developed nation would deal with man-eating crocodiles in its lakes and rivers, hungry lions killing livestock, and elephants harassing and trampling people while knocking down trees and devastating farm crops. On top of that, imagine foreign nations dictating to the United States what wildlife they could or could not manage and how it should be utilized.

Besides the everyday animal-human conflicts, African wildlife faces relentless slaughter at the hands of poachers, putting a whole other perspective on the issue. But the most daunting peril that African wildlife faces today is a rapidly expanding human population that threatens to upset the natural balance by the ever-increasing destruction and loss of wildlife habitat. Realistically, given the circumstances African wildlife faces, the situation is dire and its future is bleak without implementing serious remedies that keep the larger conservation picture and goals in focus.

The elephant situation in Botswana is a prime example of the complexities affecting wildlife. During the past 50 years, Botswana’s elephant population has expanded far beyond the carrying capacity of the land where they occur. According to NRAHLF.org contributor Ron Thompson, a qualified field ecologist and founder of South Africa’s True Green Alliance who has been working in Africa’s national parks and wildlife management systems for 58 years, “Governments in most countries have been negligent in maintaining species diversity, resulting in the loss of direction and the impetus of conservation. Today, all over southern Africa, the national parks are being managed as ‘elephant sanctuaries’—at great cost to biological diversity.

“Aggressive animal rights propaganda has contributed greatly to misinformation and confusion, causing many people to accept irrational and uninformed public opinion. Today, governments will not cull even the most excessive of elephant populations ‘because the public disapproves of culling.’ And because of that fact, every single facet of biological diversity in many national parks is being destroyed by too many elephants. If the habitat is healthy and safe from damage, the animal species will be able to look after itself with minimal assistance from man.”

But long-term goals like “biological diversity” only can be reached through coordinated efforts that incorporate several scientifically sound solutions and proven management practices. Success can be achieved with the implementation of various conservation and management practices that seek to assure the preservation of the habitat and the continued survival of wildlife. The success of a conservation effort in any given area must be judged as to a species’ overall population trend and not by the survival of individual animals. If over time some animals are killed, but the overall population of a species in that area remains stable or increases, then that conservation practice must be deemed successful.

Both non-consumptive management (photo tourism) and consumptive management (controlled, managed hunting) are needed side-by-side for conservation to achieve its full potential. Areas such as national parks are set aside for non-consumptive use and from a national perspective are specifically intended to protect wildlife and wildlife habitat. As the cornerstone of most conservation programs, African national parks clearly play a critical role.

Nonetheless, national parks only cover a fraction of the landmass where wildlife exists in Africa. In fact, in many African countries it is the areas outside these nationally protected lands that harbor more wildlife—not by density, but by total count. In Tanzania, for example, only 7 percent of the country’s land mass is allocated to national parks, whereas hunting areas make up 32 percent, thus supporting a much greater wildlife population.

Globally, the country that currently manages its wildlife resources in the most successful and scientifically sound manner is the United States, where multiple-use is the fundamental driving force behind that success.

The countries that have adopted and implemented a multiple-use approach to wildlife management are the ones that have succeeded the best at conserving their wildlife resources. Namibia is a good example of how a country that utilizes both consumptive and non-consumptive wildlife management has seen its wildlife numbers increase in recent years. Kenya, on the other hand, only utilizes non-consumptive management practices and has seen wildlife numbers outside of protected areas plummet over the same time frame. Globally, the country that currently manages its wildlife resources in the most successful and scientifically sound manner is the United States, where multiple-use is the fundamental driving force behind that success.

During the past few years, African nations utilizing multiple-use conservation practices that include managed hunting as a management tool have been specifically criticized, especially in regard to high-profile species such as lion and elephant. Trophy hunting is just one of the many types of consumptive management practices that occurs in a multi-use system, which might also include meat hunting, trapping and culling.

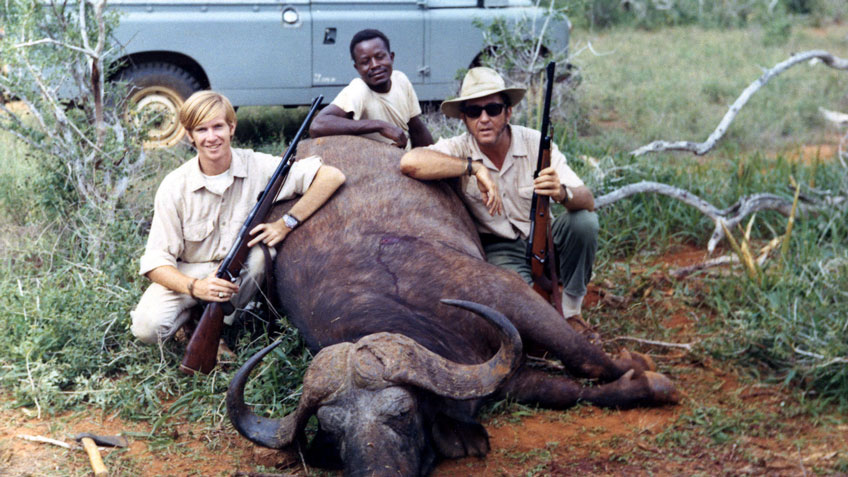

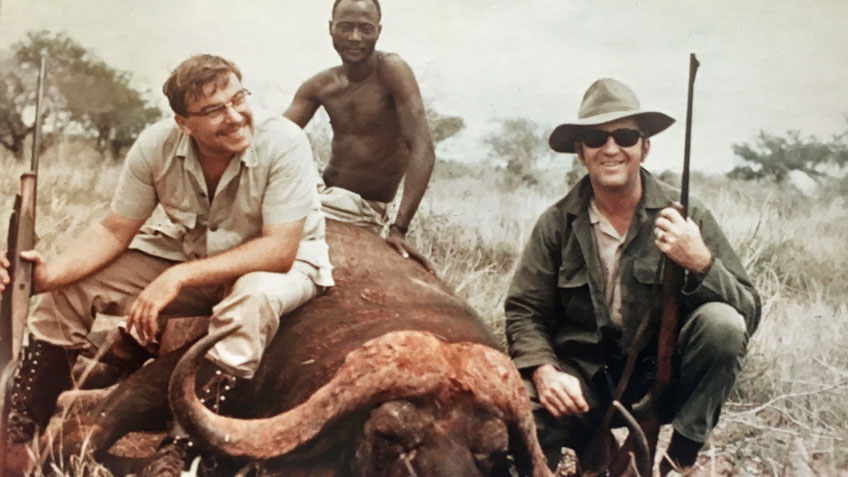

Those who hunt for subsistence, or for meat, don’t face the same backlash that trophy hunters do. Trophy hunting is often portrayed as killing for “sport” or for “fun,” which, for those who do not fully understand the significant role it plays, understandably stirs up strong emotions against the practice. However, what is most relevant when discussing the role trophy hunting plays in a conservation effort is its final effect and outcome on wildlife populations on a vastly larger scale.

Putting it simply, managed trophy hunting has minimal biological impact on the overall wildlife population, while at the same time it generates significant revenue needed to administer and conserve the species. Trophy hunting achieves this through the limited and selective process of taking only mature males, many of which are beyond their reproductive prime, and which has little or no impact on the species as a whole. Meat hunters, on the other hand, don’t normally pay large fees for taking an animal and are far less selective than trophy hunters when collecting an animal. Meat hunters often take females and younger animals, which is perfectly acceptable in circumstances where a wildlife population needs to be controlled or reduced. Trophy hunting, however, is utilized when wildlife managers want minimal impact and to allow a population to increase. Trophy animals also bring much higher fees and therefore generate more money, which is crucial for ongoing conservation efforts.

With all the recent negative hype surrounding trophy hunting, the most important conservation question is often overlooked, which is what happens to wildlife populations and habitat when trophy hunting is stopped? In 1993, Ethiopia stopped elephant hunting in the tropical rainforests of the Gurafarda region. Prior to that, Gurafarda supported around 3,000 elephants with trophy hunters taking between 10 and 15 elephants per year from that area. Within 10 years of the ban, the rainforest had been cut down and today not a single elephant exists in that vast area. Sadly, this is the kind of outcome that results from banning trophy hunting, which in effect, removes the incentive for looking after the game and eliminates the finances necessary for administering and implementing management and control of the wildlife.

Vital to the question of whether to allow hunting or not is considering what management practices can effectively replace the role and finances that are generated by trophy hunting. Merely banning hunting leaves a whole mess of problems and concerns in its wake. For instance, turning hunting areas over for non-consumptive use is rarely a feasible option, mainly because it’s difficult to satisfy the expectations of photographic tourists with thinner wildlife densities in remote areas that are tough to access and lack the infrastructure to comfortably accommodate them. And, most importantly is the fact that non-consumptive tourism is incapable of making up the difference in lost revenues once provided by trophy hunting.

As has clearly been seen in the countries that banned hunting, when the hunting areas were vacated, they became vulnerable to unchecked poaching and subject to habitat loss and destruction. Without wildlife protection (anti-poaching efforts) or habitat management in place, the outcome has been devastating in those areas—an outcome which nobody, hunters or otherwise, would wish to see.

If trophy hunting is stopped throughout Africa, wildlife will still survive in national parks and other highly protected areas. However, in the areas outside of those places, it will be devastated. Wildlife is a renewable resource that needs to be properly managed in an increasingly crowded world. Any management practice that is a proven contributor to the overall larger picture of conservation in Africa must be given a chance to fulfill its purpose, and trophy hunting is a time-proven management tool for African wildlife’s health and well-being.

About the Author: Joe Coogan spent his younger years living in Kenya, East Africa, with his family during the 1960s and 1970s. As an avid hunter, shooter and outdoorsman, his early Kenya experience prepared him for safari work for many years as a professional hunter (PH) in Botswana and Tanzania. In 1972, Coogan earned a degree in journalism from the University of South Florida, returning to Africa to work for the renowned safari firm Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safaris. He joined its Botswana operation under the leadership of the renowned Harry Selby and earned his PH license under Selby’s guidance. Coogan conducted hunting safaris in Botswana for KDS Safaris and Safari South for the next 20 years. In 1991, he joined the editorial staff of Petersen’s Hunting, relocating to Los Angeles. In 2001, following a three-year stint in Arkansas managing a wildlife project, he returned to Africa when he joined Arusha-based Tanzania Game Tracker Safaris (TGTS), conducting hunting and photographic safaris in Tanzania for the next five years. In 2006, Coogan joined Benelli USA as its brand marketing manager, hosting its popular "Benelli On Assignment" outdoor TV show for six years. Today, he is a field editor for the NRA’s American Hunter and travels between his home state of Florida and Botswana, arranging and conducting safaris throughout Africa.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]