by Keith Crowley - Monday, July 8, 2019

Terms like hardcore, extreme and even badass get tossed around a lot these days in the hunting world. In some cases these monikers are earned, but for the most part it’s just people doing things the old way—like a solo backpack hunt for elk or maybe shooting sea ducks off the Alaskan coast in a rowed skiff, or perhaps a Fred Bear-style grizzly bear hunt with a recurve bow. Any hunter worth his or her salt back in the first half of the 20th century wouldn’t have thought there was anything unusual about these things. It was just business as usual.

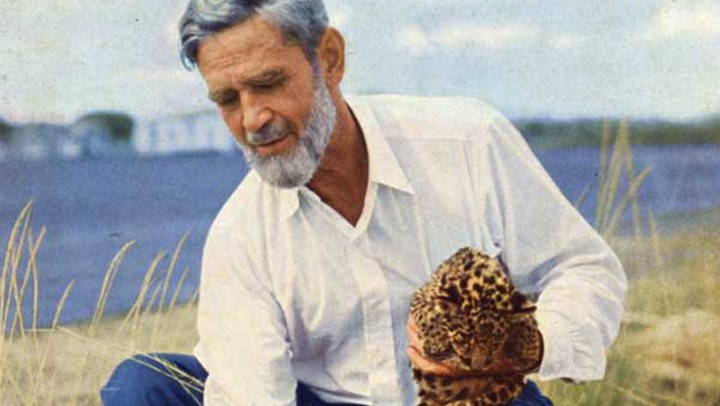

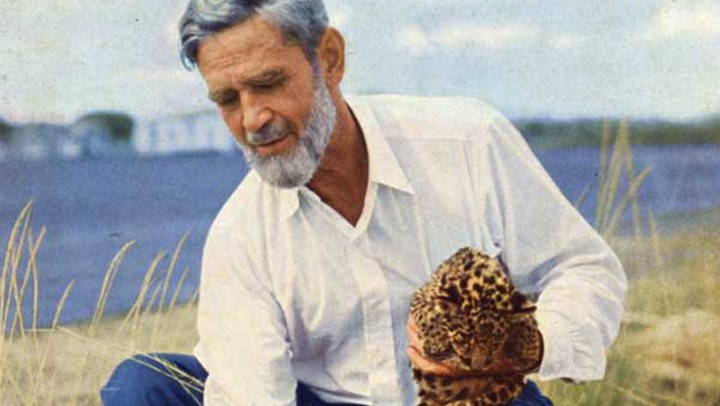

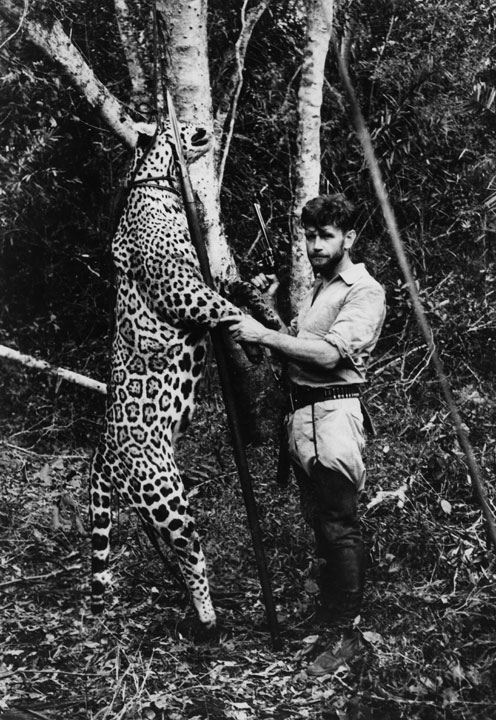

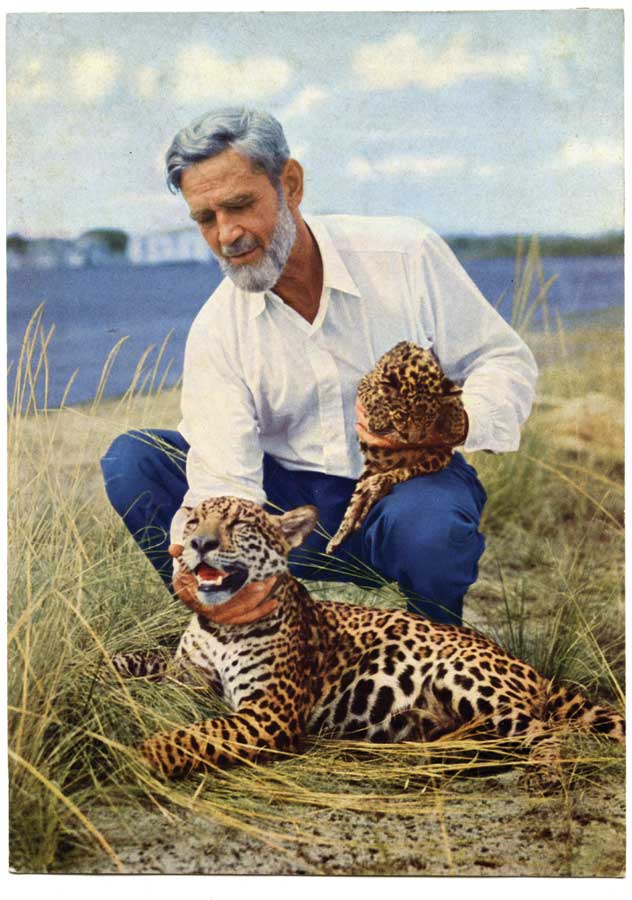

Now meet Alexander "Sasha" Siemel. Even in his day, he was something else. Every title you want to bestow on him would scarcely suffice to acknowledge his incredible hunting methods. First, you need to know that Siemel was a jaguar hunter. And that he used a spear. This wasn’t a throwing spear, by the way. It was a thrusting spear that Siemel never let go of during the hunt, even when there was a 200-pound piece of hell-fury and claw writhing on the other end. Siemel knew that to let go of the spear was to invite a brutal and certain death.

Alexander “Sasha” Siemel was born in Latvia in 1890 but had moved to the United States by the time he was 17. He stayed in the states only a short time before a job lured him to Argentina and subsequently to the Pantanal region of western Brazil where he became a mechanic in the mining camps of Mato Grosso. It was there that Siemel met an indigenous hunter named Joaquim Guato who taught him the ways of the zagaya, the 7-foot, iron-tipped spear used by local hunters to kill the jaguars and pumas menacing their livestock.

Guato was a tiny man who Siemel estimated to be about 60 years old, and the native was heavily intoxicated on a local brew when Siemel met him. It seemed impossible to Siemel that this man could kill the large jaguars of the region alone with a spear. He had to find out for himself so he joined Guato on his next hunt, which occurred the very next morning.

Siemel was an incredibly fit man, yet he had great trouble keeping up with Guato as the little old hunter skillfully wove his way through the thick jungle, following the baying of his dogs. When the treed jaguar finally dropped from the branches to face Guato, Siemel was stunned at the speed and agility the little native demonstrated.

With the cat at bay in the forest undergrowth, Guato held the spear at waist level, approaching slowly until he was within touching distance of the cat. Occasional prods with the spear point brought predictable snarls and swipes from the cat, but it was not until Guato kicked a clump of debris into the cat’s face that it finally charged. The cat lunged, the spear thrust and the cat died quickly from the blade.

It was then that Siemel determined he would learn the skill, or die trying.

Learn he did. Under Guato’s supervision, Siemel was the first non-native ever instructed in the use of the zagaya. He became so proficient with it that during the 1920s and 1930s he successfully took at least 31 jaguars and countless pumas using only the spear. Remember, this was all taking place in the densest of jungle habitat and one false blow with the spear or a loss of footing was certain to result in grave bodily harm to the hunter. Dogs, too, were often killed in the process. Guato lost his best hunting dog, Dragoa, when the cat, the dog and the blade all met at the same time during one hunt.

Ultimately, perhaps inevitably, Guato was killed by a particularly large jaguar, reputedly weighing about 300 pounds that had a distinctive track showing only three toes on one front foot. Siemel spent several years trying to find the man-killer dubbed “Assassino” by the natives, finally killing a large, three-toed jaguar in an epic struggle not far from the place Guato was killed. The killing of Assassino only raised Siemel’s standing in the jungles of Brazil. Word of Siemel’s exploits quickly spread in the United States.

Author Julian Duguid came to South America in 1929 to travel with Siemel and document some of his exploits. Duguid’s subsequent book, "Green Hell," resulted in Siemel becoming very well-known in the United States. By the late 1930s film producers arrived to turn the larger-than-life hunter into a film star. Columbia Pictures, along with legendary hunter and animal collector, Frank “Bring ‘Em Back Alive” Buck made a 15-part serial called “Jungle Menace” with Siemel cast as “Tiger Van Dorn.”

Siemel soon began a U.S. lecture tour. During one such lecture in Pennsylvania he met his future wife, Edith Bray. She joined Siemel in Brazil for several years, but ultimately, she lured him back to Green Hill, Pa., where Siemel bought a small farm and opened a museum surrounding his exploits. He and Edith also wrote articles about their life in the jungle for publications including National Geographic, Argosy, Colliers and Field & Stream.

Siemel continued to lead tours of the South American jungles into the 1960s but ultimately retired permanently to the Pennsylvania farm. There he penned his autobiography, "Tigrero." At one point, Darryl F. Zanuck of 20th Century Fox purchased the screen rights to Siemel’s book and intended to turn the story into a Hollywood blockbuster starring John Wayne as “Tigrero,” the guide and hunter. Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner were meant to round out the cast. Ultimately, the studio, (or more likely its insurance company) decided the on-location shooting would be too dangerous for the A-list stars, and too costly for the studio, so they canceled the project.

During his lifetime, Siemel’s story was featured in Reader’s Digest, Life magazine and even The New York Times. Time magazine profiled him seven times between the 1930s and 1950s. Can you imagine publications like these running similar character studies today? I certainly can’t.

For a man of multiple death-defying adventures involving the taking of an estimated 300 big cats, it seems like an odd counterpoint to his life that he died peacefully in his sleep at his Pennsylvania home on Feb. 14, 1970 at the ripe old age of 80. Sasha Siemel truly was the hardcore, extreme, badass hunter of his generation.

To read the story of Siemel in his own words, Safari Press will re-release the out-of-print autobiography "Tigero" in the fall of 2019.

About the Author: Keith Crowley is an award-winning writer and photographer and the author of three books on the outdoors: “Gordon MacQuarrie: The Story of an Old Duck Hunter,” (2003), “Wildlife in the Badlands,” (2015) and the newly released “Pheasant Dogs.” When he is not traveling in search of new stories and new images, you can find him at his home on a lake in northwest Wisconsin with his wife, Annette, and a collection of old dogs and old boats.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]