by Tim Richardson - Tuesday, October 21, 2025

Editor’s Note: One of the rewards of working for the NRA for 30 years is the opportunity to partner with hunting and wildlife conservation colleagues and like-minded organizations to create measurable outcomes in sustaining wildlife and their habitats and the outdoor traditions we NRA members cherish. I was struck by the impact of our collective efforts once again recently when I crossed paths with friend Tim Richardson of Wildlife Forever. “Karen, the NRA deserves to take a bow this year,” he said, with enthusiasm. “It was 30 years ago that NRA’s support for conserving the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge using Exxon Valdez penalty funds was a tipping point in the region’s recovery.”

Considering one would have to be 40-plus years old to recall the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 when the tanker ran aground in Prince William Sound, Alaska—spilling 11 million gallons of crude oil—he added, “That means few people know anything about how the $1 billion Clean Water Act fines were obtained and spent—and only a handful of NRA members know your organization’s support was decisive and instrumental.”

So, here is the NRA’s story—how an organization backed by millions of conservation-minded members helped to turn tragedy into lasting protection for Kodiak’s wild lands.—KMP

■ ■ ■

The year 1989 was monumental. Top media stories included the creation of the worldwide web, the fall of the Berlin Wall, China’s crushing of the Tiananmen Square dissent and the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

For the wildlife conservation community, the 11-million-gallon crude-oil spill in the pristine waters of Alaska’s Prince William Sound caused extensive harm to fish and wildlife and would be a foremost concern for years. On top of the shock and disgust the public expressed over the then-largest environmental disaster in U.S. history, America’s conservationists and environmentalists advocated for maximum Clean Water Act pollution fines and other penalties to be paid by Exxon, the world’s largest oil company.

With economic damages and clean-up costs handled in separate lawsuits totaling $4 billion, the environmental damages case rested on criminal and civil prosecutions of Exxon by President George H.W. Bush’s Department of Justice and Alaska Gov. Walter Hickel’s Department of Law. No one was certain of the extent to which the Bush and Hickel teams would push, and the “active litigation” status created a cloud of silence.

Around the first anniversary of the oil spill, Gov. Hickel said, “Let’s merge the state and federal lawsuits and insist on a $1 billion settlement from Exxon, or we’ll see them in court.” The stiff jab by Hickel, a former Golden Gloves champ, worked. The nation’s then-largest environmental fine was reached in October 1991, a year and a half after the spill, though how the settlement would be spent was unknown. The $1 billion in funds represented 20% of Exxon’s annual profit. The state and federal governments each would receive $50 million in the criminal settlement that they alone would control. The far larger $900 million civil settlement was to be spent by a six-member Exxon Valdez Trustee Council.

Alaska’s three of the six trustees represented the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation and the Department of Law. The three federal trustee agencies chosen were the U.S. Department of Interior, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Federal Judge Russel Holland’s civil-fine terms stated that all Trustee Council spending had to be unanimously approved with a 6-0 vote. From its organizational baby steps at the end of 1991 to slow walking at the start of the 1992 presidential election year, every imaginable public and private stakeholder circled the $1 billion with an opinion on how to spend it. Preoccupation with the presidential election resulted in a full year of inaction following the October 1991 Exxon settlement. Bill Clinton and Al Gore won the three-way presidential race with 43% of the vote, leading to a switch of the three federal trustees.

Fortunately, then-Secretary of the Interior and former Arizona governor Bruce Babbitt grabbed the federal team’s reins to the delight of conservation advocates hoping to maximize the outcomes of Exxon’s $1 billion penalty. But the hopeful mood soured when Gov. Hickel threatened on the fourth anniversary of the spill to wait out Clinton’s first term, barring more middle ground on a wide range of Alaska development issues involving federal lands, including oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Gov. Hickel’s threat was real because the three Alaskan oil spill trustees were cabinet appointees serving at his direction. On the federal side, the chain of command ended at President Bill Clinton’s desk. The frustrated oil spill restoration community saw the state-federal fault line going from crevice to chasm.

During an August 1993 visit to Alaska, Babbitt’s Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks George Frampton proposed a grand bargain with Alaska Attorney General Charlie Cole. Frampton said that Secretary Babbitt’s top priority for the federal share of the $900 million civil settlement was “conserving habitat with purchases or easements of every private inholding owned by a willing seller in the nearly two-million-acre Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge (NWR).”

This drew the immediate attention of the conservation community as the Kodiak NWR spans 1.9 million acres, accounting for more than two-thirds of Kodiak Island, part of Afognak Island and all of Ban and Uganik Islands, and is a noted sanctuary for a diverse range of wildlife including the iconic Kodiak bear, the largest recognized subspecies of brown bear, found exclusively on the islands in the Kodiak Archipelago where it has been isolated from other bears for nearly 12,000 years.

Those private inholdings totaled more than 350,000 acres and included the banks of 70% of the refuge’s salmon rivers. Alaska Native corporations owned nearly all the inholdings and were willing sellers of fee title or conservation easements. Native corporations owned more than twice that acreage on forested Afognak Island in the Kodiak Archipelago.

One Native condition on the sale of any Kodiak NWR inholding was that high-value salmon river riparian areas be paired with low-value mountainside tracts that they were forced to select by Congress under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971.

Some opposed Native Alaskans in the spill region getting a disproportionately large amount of the funds and some Native corporation shareholders opposed any sale of ancestral lands. Kodiak also was the area least directly harmed by the spill that started in Prince William Sound 240 miles away.

Public access rights to Kodiak’s world-class areas were the tradeoff Babbitt’s plan offered. The federal plan was bolstered when biological assessments of oil-spill-injured wildlife and habitats within 1,200 miles of coastal areas in the spill region demonstrated that the Kodiak Archipelago had 75% of the top ranked habitat parcels.

The Alaska trustees’ reluctant support of Kodiak habitat acquisitions was paired with Gov. Hickel’s Seward Sea Life Center, intended as a cruise ship tourism attraction but it conducted enough Gulf of Alaska marine research to qualify for oil spill funds. Hickel said Alaska needed its own “Woods Hole” marine science center comparable to the premier science institutions in Woods Hole, Mass., and wanted to boost the spill region’s economy.

When the proposed dual agreement went public, environmental groups favoring forest acquisitions from Native corporations in Prince William Sound sharply attacked it. The Sea Life Center was decried as a “whale jail” representing brick-and-mortar restoration designed for tourism using funds meant for the damaged Prince William Sound environment. They had a strong case.

Enter the NRA

It was at that moment that numerous conservation groups stepped up to back Babbitt’s plan. Helping to lead the charge was the National Rifle Association and its millions of members.

“In short, Kodiak is special to our members,” an NRA statement explained. “As a National Wildlife Refuge, it provides millions of acres of spectacular landscape and wildlife available to hunters and sportsmen. Preserving its future is our primary objective from the Exxon Valdez process.”

These words were echoed by two members of the NRA Board who also happened to be influential senior members of Congress and co-chairs of the Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus. In a joint statement, NRA Life members Rep. Don Young (R-Alaska) and Rep. Bill Brewster (R-Okla.), wrote, “The Kodiak Refuge is one of the nation’s oldest and more famous refuges and yet it faces challenges to its management integrity. Foremost among threats to the refuge is loss of public access to the most prized sport hunting and fishing areas, as well as commercial development of prime bear habitat.”

NRA leaders, Reps. Young and Brewster and the NRA’s millions of members believed the public and the region’s fish and wildlife resources would be well-served by taking such action. This high-level NRA support for the Kodiak region was by far the most impactful among the more than 30 sportsmen’s conservation group endorsements for the federal plan.

While hunter and angler groups argued forcefully for breaking the multi-year oil spill settlement impasse in favor of investing the funds in public access wildlife habitat acquisition, they won over enough green group leaders to create a clear pro-habitat consensus for Kodiak.

As the NRA noted, the Exxon Valdez oil spill settlement had to be rescued immediately or else “large-scale conservation as a mission would lose public faith,” adding that “Kodiak offers landscape scale habitat protection as a proper use of the largest environmental fine in U.S. history.”

Amid the challenges to conservation at hand, Rep. Young—as Alaska’s sole congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives—sent a rebuttal to the Anchorage Daily News over a 1995 editorial challenging the fair prices paid to Kodiak Native Corporations participating in habitat restoration land sales and conservation easements. “If Alaska is to grow economically, culturally, spiritually, we’ve got to do better than what I saw coming through in your editorial,” he wrote, sharing that Alaska Native corporations provide a significant employment base throughout the state, creating jobs for both Natives and non-Natives.” Adding that the Kodiak projects were a win all the way around, he explained, “They are good for the wildlife. They are good for the fisheries. They are good for hunters and anglers. They are good for the people. They are good for business. … They will not only conserve some key habitat but stimulate development just outside the refuge that will generate economic benefits to the region from now on.”

Kodiak land sales and easement advocates also pledged support for all the forest resource conservation possible within Prince William Sound—something for which the NRA also deserves credit.

So, NRA members should take a bow this year. It was 30 years ago that the Exxon Valdez settlement set records for wildlife refuge habitat purchases offering public access on the spectacular Kodiak NWR. The subsequent large purchase deals in Prince William Sound and the Kenai Peninsula to permanently conserve habitat also set records for refuge, forest and park conservation.

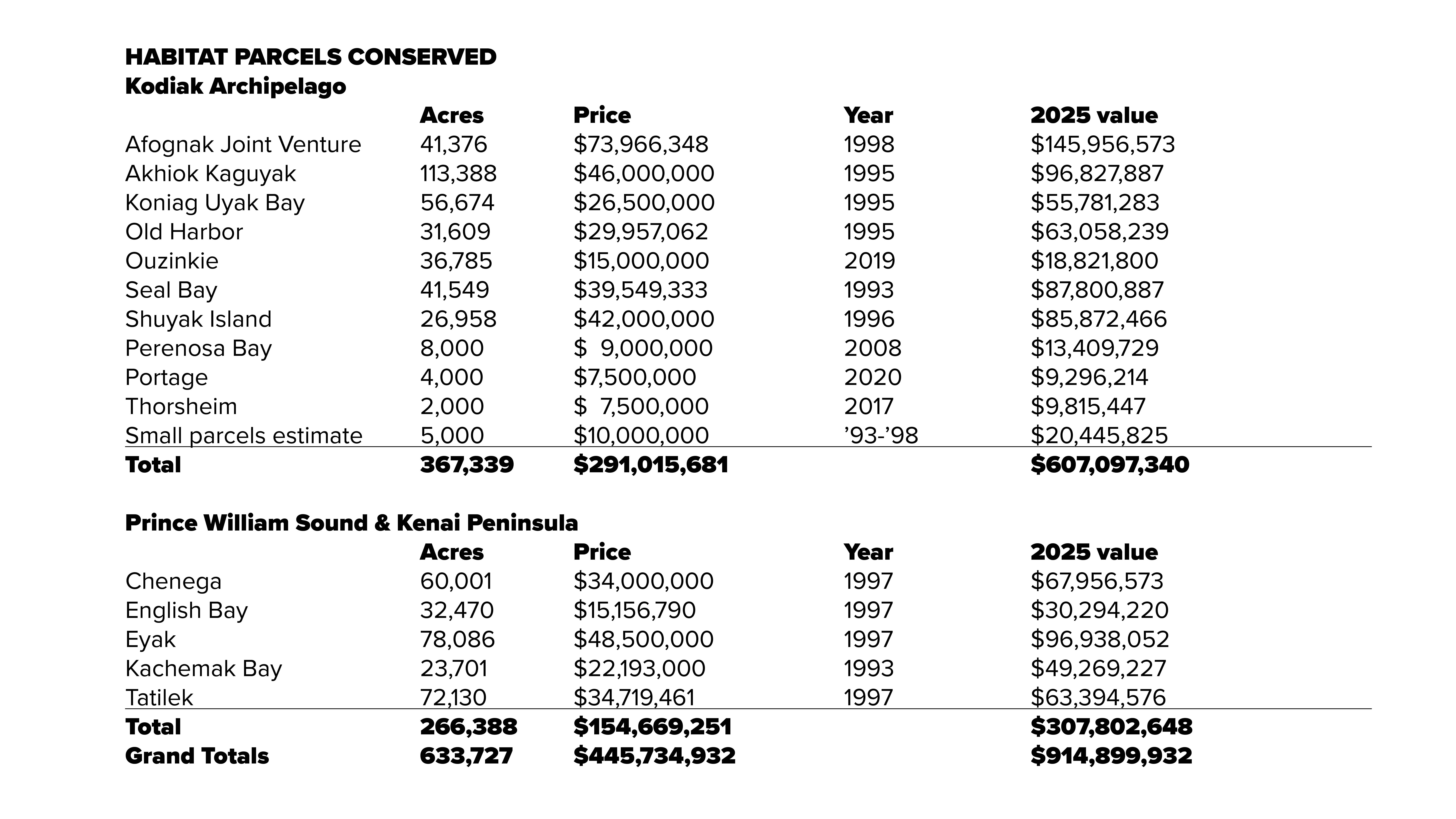

Habitat Parcels Conserved through Exxon Valdez Lawsuit Funds

As detailed in the following chart, the NRA-supported conservation agreements using Exxon Valdez funds totaled 633,727 acres costing $445,734,932 with a current inflation-adjusted value of an incredible $914,899,932. We NRA members take pride in the fact all but 5% of these acres are open to world-class public outdoor recreation including hunting, fishing and camping. The conserved lands were mostly Alaska Native corporation inholdings within federal and state conservation areas totaling 7.4 million acres.

A Special Thanks to the NRA

In acknowledging the impact of the NRA and its millions of members 30 years ago, American hunters and conservationists must give credit where it is due. The bottom line: The NRA succeeded in helping to make sure America’s state and federal decision makers directed the bulk of state and federal Exxon Valdez oil spill funds toward buying all the fish and wildlife habitat for sale in Prince William Sound and the Kenai Peninsula for public use, including hunting.

These efforts ultimately influenced the U.S. Department of Justice and Congress to create a $20 billion settlement and restoration plan after the Deepwater Horizon oil rig disaster of 2010. History shows that the NRA not only played a pivotal role in shaping the outcome of the Exxon Valdez disaster—at the time the worst environmental accident in U.S. history—but the lessons learned by state and federal governments in conjunction with the NRA’s leadership have created a “through line” that continues to influence Deepwater Horizon disaster efforts.

Thank you, NRA.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.