by Karen Mehall Phillips - Thursday, June 6, 2019

As we hunters unite to address the culture war on hunting, any seminar providing insight on how to debate and communicate effectively about our hunting heritage is welcome news. To save hunting’s future, we first must build our communications skills—learn to push back against those seeking to end hunting, reach those in the middle who are not against us but who have never been exposed to our way of life, and set the record straight. The hunting community already has scientific facts on wildlife management and the truth on its side, yet too often hunters cannot score points in a debate on the merits of legal, regulated hunting or its value as the world’s No. 1 wildlife management tool simply because we do not have the strategic thinking and communications skills to win it. Fortunately, the tide is turning.

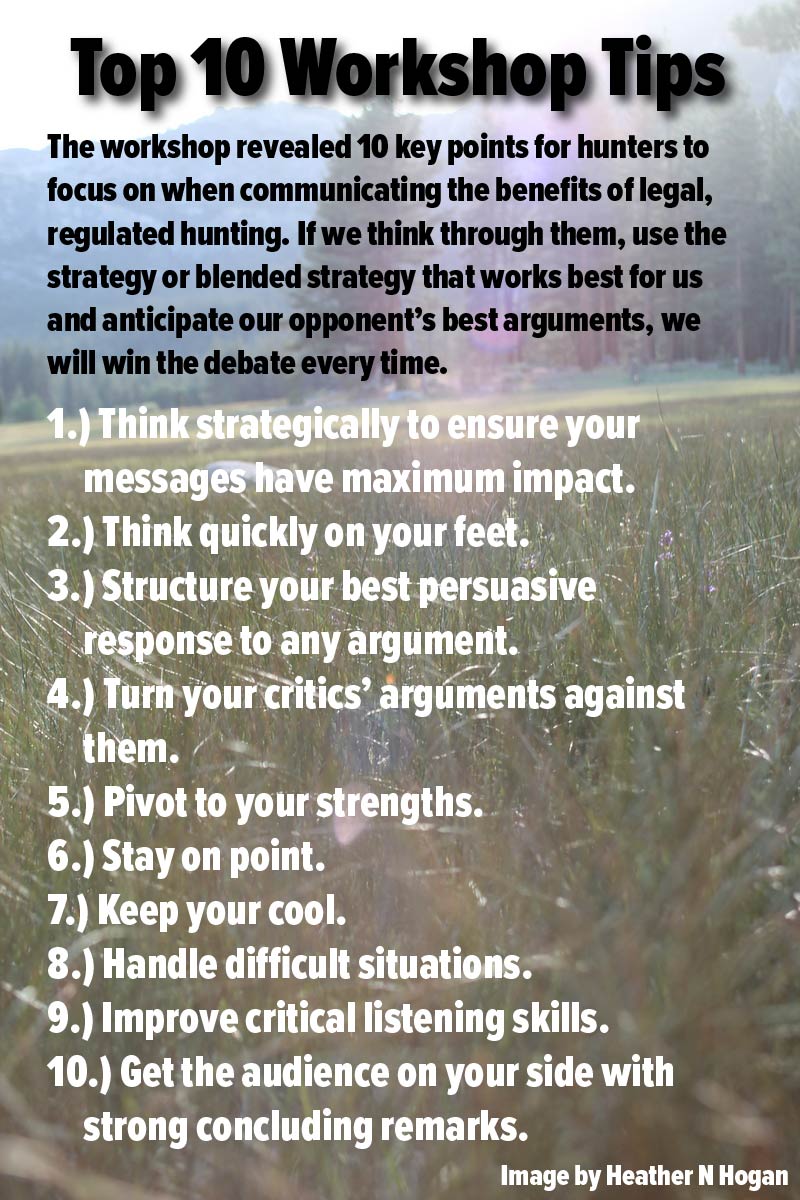

On May 15, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF) and internationally known natural resource and outdoor recreation survey and research firm Responsive Management (RM), in partnership with the NRA Hunters’ Leadership Forum (HLF), held an inaugural “How to Debate and Communicate Effectively about Hunting” workshop near NRA headquarters in Virginia. The sold-out event drew nearly 100 people from state fish and wildlife agencies and like-minded non-governmental hunter-backed organizations. A culmination of a year-long Multistate Conservation Grant study initiating research on communications strategies to increase support for hunting, the workshop was funded through the Wildlife Restoration Program administered by the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

The goal: to institutionalize the right way forward to protect hunting’s future, starting with teaching pro-hunting audiences to use winning debate tactics to communicate hunting’s benefits and build long-term support.

The foundation of the multistate grant study and workshop was the NRA’s ground-breaking NRA HLF-funded study “How to Talk to the American Public about Hunting.” In 2016, the NRA hired RM Executive Director Mark Damian Duda to conduct one of the first comprehensive national survey and focus group studies examining public attitudes toward animal rights, animal welfare and hunting. Public attitudes control the debate, and the hunting community needed benchmark data to gauge public perceptions to begin crafting messages that resonate with non-hunters. In January 2019, RM worked with the National Shooting Sports Foundation on a similar study titled, “Americans’ Attitudes toward Hunting, Fishing, Sport Shooting and Trapping,” which underscored the NRA data, documenting America’s overwhelming support of hunting (conditional to hunting method and species). The workshop took into account a supplemental NRA HLF-funded study from earlier this year revealing more than 80 pro- and anti-hunting responses explaining why participants support or do not support hunting. Each was then tested in surveys with more than 15,000 Americans. It pinpointed the most and least effective pro-hunting arguments and counterarguments that resonate best with non-hunters.

“We now have data on how to defend and debate hunting in the most effective manner,” said Duda, who spearheaded getting the grant funding needed to test and then rank the issue arguments made for and against hunting. “The research shows which arguments resonate most in increasing support for hunting.”

The workshop tapped the services of Samuel Nelson, director of Cornell University’s debate team—the No. 1 debate team worldwide—and a noted expert on argumentation and persuasive communication. Nelson wasted no time conveying the challenge of thinking strategically and arguing effectively, kicking off the workshop by holding a few mock debates with participants, playing the role of the anti-hunter.

Next up, Duda presented the results of the study’s message testing, breaking down the most effective pro- and anti-hunting arguments. NRA HLF website (NRAHLF.org) contributor, attorney and author Michael Sabbeth then honed in on the value of increasing hunters’ debate skills. His point: We already win on morality, science and facts. We will win in debates once we enhance our communications skills.

The research was then put into practice, guided by Nelson and his business partner, John Stowell, who brought real-world experience in messaging and strategic marketing through work with major national brands. Participants practiced debating amid lessons on how to best to frame issues, engage audiences to be on hunters’ side on issues, and maximize the hunting community’s credibility—whether the one going on offense to advocate for hunting is a mainstream American hunter or a representative from a hunting organization or state wildlife agency.

Sample Strategies

As far back as 350 B.C., Greek philosopher Aristotle knew truth did not speak for itself. Nelson said Aristotle understood that to persuade, one needed three things: ethos—credibility and trustworthiness; pathos—empathy and an ability to appeal to emotion and make people care; and logos, or logic—validity. He then referenced modern-day philosopher Stephen Toulmin (1922-2009), who, throughout his writings, sought to develop practical arguments that could be used effectively in evaluating the ethics behind moral issues. Toulmin also said you need three things for a good argument: a claim—thesis or a point; a warrant—justification or reasoning; and data—the proof. American hunters have all three.

PCAN (Problem, Cause, Answer, Net benefit) Method

While "The Art of War" by ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu sheds light on defeating one’s enemies, Nelson wins them over through "The Art of Woo: Using Strategic Persuasion to Sell Your Ideas," where authors Richard Shell and Mario Moussa promote the PCAN (Problem, Cause, Answer, Net benefit) method. First, one must explain that there is a problem and that he or she understands the cause, which enhances credibility. “If you understand the problem, you know what you are talking about and people may be persuaded,” Nelson said. The answer is the solution. As for net benefits, “The more additional reasons you give, the greater chance one will be persuaded”—a move used in sales all the time. When a product comes with countless accessories, how can one say no?

IBM (Identify, Beat, Mean) Method

“Identify the argument I’ll respond to, beat their best argument and mean it by sharing why my argument is important—IBM.“ Translation: “Explain why it’s important to care about hunting and view it like you do, or else we will lose the best tool for wildlife conservation.” For example, Nelson used antis’ argument asking how we can love animals but then hunt them. “If we eat and need meat, we have to kill,” he said. “It’s important to understand how the world works and why we have to kill animals.” Hunters must recognize that some people have no point of reference as they never have seen an animal killed. Recognize this when crafting arguments.

Tricks of the Debate Trade: Ponder These Nine Questions in Advance

1.) How can I think strategically about making my messages have their best impact?

Anticipate the other side’s best argument. (It likely will be an offensive, principle-based argument about why hunting is unethical and a defensive, consequences-based argument such as that hunting is ineffective in preserving the environment.) Then frame your answer. For example, frame hunting as nurturing and promoting the environment via regulated conservation. Note that animal rights extremists constantly compare things to what we know—the same way one might make sense of a new fruit juice because he or she already knows of orange juice. Nelson says anti-hunters often compare ranching/farming to slavery. “They [antis] try to make a frame about there being no difference between humans and the animals raised, but once you lose the frame, you lose the debate.” How we talk about something is important because of this framing. “This is why those for abortion rights don’t say ‘I’m pro death,” he says.

2.) How can I enhance my ability to think quickly on my feet?

Assess your competence in the specific interaction. Can I give a specific response? If yes, give it. If not, retreat to your first principles. Identify the question you want to answer, repeat the question then answer it.

“For example,” Nelson says, your response might be “the real question is if hunting is effective in ensuring animal populations are neither under- nor over-populated. The answer is overwhelmingly yes. Hunters work within the parameters of local wild game regulations to ensure balanced conservation.” Nelson, who regularly consults political candidates, explains that some politicians don’t answer the question because they don’t know the answer. “It’s okay to say ‘the bigger question is’ or ‘here’s what this debate is really about so I answered the important question.’”

And take low-hanging fruit, he says, such as by addressing problems associated with invasive wild pigs in states where they are destroying agriculture and habitat. Explain why your opponent’s frame does not work.

3.) How can I structure my best persuasive response to any argumentative attack?

Think PCAN or IBM. For example, anti-hunters argue hunting is bad because it causes accidents. Explain this is not an argument about a harm intrinsic to hunting but rather improper hunting procedures. Better regulations and promotion of safe hunting practices address this harm. For the overall debate, this perceived disadvantage to hunting is relatively small and is outweighed by hunting’s broader wildlife conservation advantages and spillover benefits to society. Explain that this should make your opponent support your cause even more.

4.) How can I turn critics’ arguments against them?

Use offensive, not defensive arguments to capture their argument. Try a “link turn” by saying the thing you think we cause, we prevent or the thing you think we increase or decrease. Or try an “impact turn” by saying the thing you think is bad is actually good. For example, he says, “You want to decrease meat eating, but that is a bad thing. You are healthier if there is more meat in society. Most vegan societies are not vegan by choice.”

5.) How can I eloquently pivot to my strengths?

Analyze the audience and appeal to credible and scholarly sources such as conservationists Aldo Leopold or U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt or wildlife officials in uniform. For example, as in the national “Hunting Is Conservation” debate in New York City covered by NRAHLF.org in 2016, explain to your opponent that he or she misunderstands the fact that hunting is intertwined in conservation. “Explain that your opponent is the one making the illogical argument as hunting and conservation have always been tied together,” Nelson says.

6.) How can I focus on what matters and stay on point?

Classify arguments as either offensive or defensive. Offensive flips arguments in your favor. If they stand alone, they win you the debate while defensive arguments mitigate their arguments.

As for the claim that hunting accidents are a problem, offer statistics documenting that accidents are infrequent, making their argument less powerful. “A single offensive argument can flip an entire part of a debate in your favor,” Nelson says, “but a few defensive arguments are necessary to sufficiently mitigate opponents’ claims. Redirect the debate to your terms while respecting their right to think differently. Nelson says the strongest argument is “I respect your right” so he suggests saying, “I respect your choice not to hunt, or your right to be vegan. I’d appreciate it if you’d respect my right to hunt.” While grabbing the moral high ground, invoking the assumption of reciprocity makes the other side look bad. Put a flaw in their argument for not respecting your choice to hunt. And do not fall for a “red herring,” he says, referring to how opponents try and change the subject to get you off track. Explain that the other topic is a different debate.

7.) How can I effectively interact with difficult people?

Listen to your opponents carefully, identify their argument then acknowledge their contribution.

For example, your recognition can be to repeat a part of what they said that resonated with you to avoid sounding patronizing or just thanking them for contributing to the conversation. “Respond to their argument, not to the person,” says Nelson, “and avoid generalizations and ad hominem attacks. For example, say, “I honestly appreciate that you care for animals. At least we agree that animals are important, but I think we should apply science, which has proven effective.”

8.) How can I improve my critical listening skills?

Identify the frames used by the other side. Take notes during the debate and keep track. Outline the structure of opponents’ arguments, marking transitions to distinct arguments.

9.) How can I get the audience on my side with strong concluding remarks?

Start by offering competing and alternate frames by which the debate should be evaluated. Do not let opponents rank which arguments matter most or control perception. Do a quick analysis and then demonstrate overlap with other stakeholders in society. “But have your own frame and do not allow them to get away with their frame,” Nelson explains. “They won’t say they don’t want wildlife conservation or freedom. They want you to say you just want a head on your wall.”

About the Author:

Karen Mehall Phillips is the communications director of the NRA Hunters’ Leadership Forum website and social media initiative and senior editor of NRA’s American Hunter. An avid rifle and bow hunter, she has hunted for 30 years and in 29 states, Canada, Italy, Finland, Germany, Spain, New Zealand, Greenland and Africa, including for two of the Big Five.

Karen draws on her experience to educate non-hunters on the critical role that hunters play in wildlife conservation worldwide and to inform them of the dangers anti-hunting extremists present to the future of wildlife conservation. She is invested in fighting America's culture war on hunters and hunting and works to shed light on anti-hunters’ blatant attempts to tout emotion and misinformation over scientific facts.

An NRA Endowment member, Karen worked in the NRA public relations arena prior to joining NRA Publications in 1998. She is the founding editor of two NRA official journals: America's 1st Freedom and Woman's Outlook. National writing awards include being named the 2015 Carl Zeiss Sports Optics Writer of the Year. She actively promotes women and families in the outdoors. She is also a member of the Washington metropolitan area's Fairfax Rod & Gun Club, a founding member of the Professional Outdoor Media Association, a member of Safari Club International and a Life member of the Dallas Safari Club and the Mule Deer Foundation.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.