by Jim Heffelfinger - Sunday, April 14, 2019

Mention zombies and everyone sits up and takes notice. The topic of zombies has become a fun intellectual pastime in the last decade. As proof, look no further than the nearest selection of popular TV shows, blockbuster movies, green-tipped bullets or lime green AR-15s. The recent reference to deer zombies infected with chronic wasting disease (CWD) in the media is neither accurate nor appropriate, but it was successful in sparking a much-needed discussion about the seriousness of the condition.

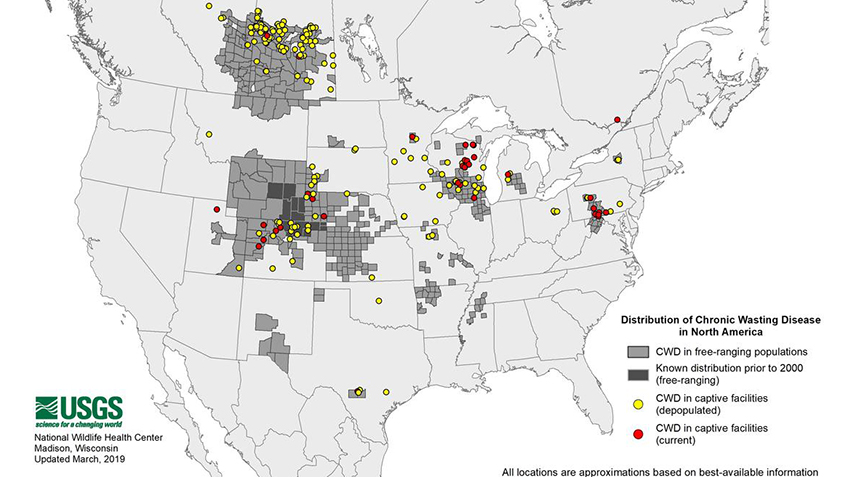

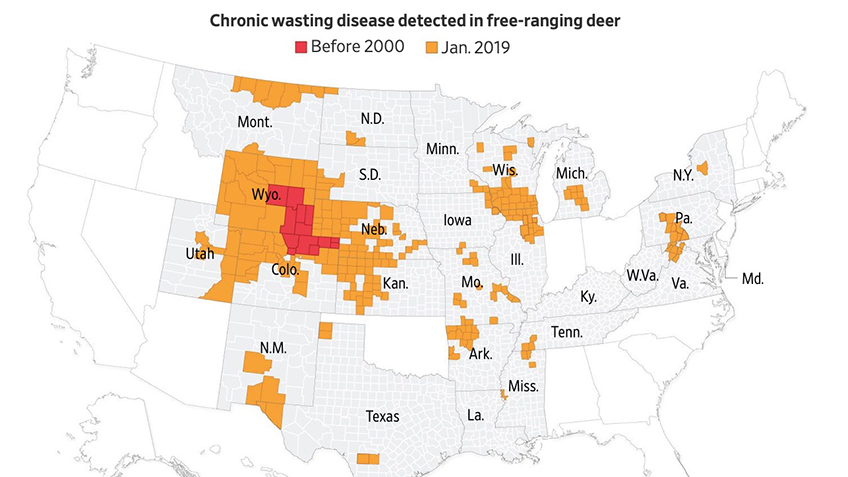

This disease of the deer family caused by misfolded proteins called prions (PREE-on) is now found in 26 states, two Canadian provinces, Norway and South Korea. What is so concerning is the fact that there is no cure and animals die within two to three years of being infected. Some infected animals will not test positive for almost two years, but shed infectious prions seven to 11 months before showing any physical signs of the disease.

Thankfully, there is no evidence CWD can infect humans, but wildlife and human health officials worry about it eventually breaching the deer-human barrier through consumption of the deer we harvest. There is no way of knowing if that is even possible, but the greater the geographic distribution and the higher the prevalence rate, or percentage of the deer population infected, the better the chances of that happening.

The prevalence rate of CWD in mature bucks in at least one Wyoming game management unit has reached as high as 40 percent. This means the chance of your buck being infected in those areas is literally almost a coin toss. Research shows that CWD negatively affects overall deer abundance when prevalence is high, meaning greater than 20 percent, but even lower prevalence can impact the rate of reproduction and survival in more subtle ways. If we don’t get a handle on the disease before it starts to affect deer abundance over large areas, we may never be able to put it back in the box.

More disturbing than the prevalence rate is the upward trend and geographic spread to new areas. The percent of the population testing positive in some units in Wyoming and Colorado has increased two- to 10-fold since the early 2000s. About 70 percent of Wyoming’s deer hunt areas are positive for CWD. More than half of Colorado’s deer herds are also infected, as are one-third of that state’s elk herds. Remember, this is the state with the largest mule deer and elk populations in the country. Colorado Parks and Wildlife has good information from various deer management units that strongly indicate units managed for an older age structure, more bucks on the landscape, and higher buck-to-doe ratios had the largest increase in prevalence over the last 15 years, while those managed for higher buck harvest remained stable or declined. This makes sense because we know disease spreads faster in higher-density populations because of more interaction between deer and a concentration of infectious agents in the environment. We also know this disease is more common in mature bucks. Most people agree that if we can keep CWD from spreading and becoming more common in the wild, we should, but it’s sobering to think about what that really means. The reality is that fewer deer on the landscape, a younger age structure, and lower buck-to-doe ratios are the conditions that probably minimize the spread of CWD.

We will always need to know more about the disease and, toward that end, bills have been introduced in the House (H.R. 6272) and Senate (S. 3644) to provide more funding for needed research on factors influencing the transmission of the disease. However, we cannot wait around perpetually calling for more funding and more information before we try to do something while the disease continues to spread and increase in prevalence. Now is the time to decide of we are going to get serious about combating the disease or just sit back and watch it unfold further—an approach that has not worked very well over the last 40 years.

State wildlife agencies have a responsibility to manage our big game herds in a sustainable way for future generations. Colorado has been researching and managing herds with CWD for decades, and in 2019, increased its CWD management efforts with a scientifically supported Chronic Wasting Disease Response Plan. The plan was developed with full engagement of the public and the nation’s leading CWD experts.

As unpalatable as some management options seem, we have to decide soon if we are going to fight the disease or pretend it’s not a problem. The Colorado plan calls for a change in management only when prevalence exceeds 5 percent in adult (2 years old or older) males. A hard look at the data shows that is the level at which prevalence seems to start increasing exponentially in a population. In other words, that is the point at which it increases at a higher rate and is hard to get under control with any kind of management action. When CWD prevalence exceeds 5 percent in adult males, the plan offers several ways to manage CWD at the deer population level: 1.) reduce deer density; 2.) reduce buck-to-doe ratios; 3.) change age structure to more younger bucks; 4.) target hotspots identified in the surveillance program; and 5.) remove sources of deer concentration.

Nearly three of every four deer units in Colorado is above the management range for buck-to-doe ratio that was established with public input. Many of these herds are also over the 5 percent prevalence threshold and thus qualify for CWD management. Regardless of prevalence, these herds should see an increase in buck harvest to bring them in line with buck-to-doe-ratio objectives anyway, but being over 5 percent only compels managers to reduce buck-to-doe ratios to the lower end of the agreed upon range. Obviously, all herds should be managed so prevalence rate never gets to the 5-percent level, which for Colorado, triggers management action.

A few other states with high rates of CWD infection are also looking seriously at deer management changes to reduce the spread and prevalence of CWD. Hunters have always supported conservation practices that were necessary to assure the sustainability of our natural resources, but we have tough choices ahead as we move to come to grips with the latest CWD information. Summoning zombies to describe CWD may draw media attention to this issue, but does more to distract than to educate. As hunters, we must understand the seriousness of this disease and be willing to support what needs to be done to preserve our heritage and our leadership role in conserving wild animals in wild places for future generations.

Editor's Note: NRAHLF.org has been reporting on CWD from the inception of the website. Recently, for example, in January 2018, the site covered how hunters in South Dakota worked with the National Park System to cull elk to curtail the spread of CWD. In March of 2018, the site reported on the launch of a five-year study in Wisconsin that aimed to look at whitetail deer survival rates in an all-encompassing manner that included both CWD and predators. In October of 2018, Rob Keck interviewed NRAHLF Co-Chair Ward "Trig" French for Bass Pro Shops Outdoor World. The first topic of discussion was CWD, and French emphasized how imperative it was that action be taken to stem the tide, because with hunting's dependence on deer, CWD could conceivably take out hunting along with the herd. That same month, the site published a story on whether humans could contract CWD by consuming infected deer meat.—Erin C. Healy

About the Author: Jim Heffelfinger is a certified wildlife biologist with degrees in wildlife management from the University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point and Texas A&M University—Kingsville. He has worked as a biologist for the federal government, state wildlife agencies, universities and in the private sector in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. He has authored or coauthored more than 220 scientific papers, book chapters and popular articles in national and regional publications. He is currently chairman of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies “Mule Deer Working Group” made up of one mule deer expert from each of 23 western states and Canadian provinces. Jim wrote the TV scripts for the mule deer, coues whitetail and pronghorn episodes of “Leupold’s Big Game Profiles,” which aired on the Outdoor Channel. Jim also wrote scripts and appeared in episodes of “Boone & Crockett Country” on the Outdoor Channel. The Mule Deer Working Group helped produce the program “Mule Deer: Saving the Icon of the West” that aired on the Sportsman Channel. He is a full research scientist at the University of Arizona, professional member of the Boone and Crockett Club, and currently works as wildlife science coordinator for the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.