by Keith Crowley - Wednesday, July 21, 2021

I don’t know about you, but when I hear the words “Hemingway” and “hunting” together in the same sentence, the image that comes to mind is Africa. Ernest Hemingway’s exploits in British East Africa with legendary professional hunters Philip Percival and Bror Blixen are the stuff of legend. Hemingway made the stories legendary with his 1935 book, “The Green Hills of Africa,” and short stories like “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.”

But there is another side to Hemingway’s hunting life, a side he never wrote about directly for public consumption, although it comes across in several of his most famous novels. That was Hemingway’s time spent high in the Rockies, straddling the Montana/Wyoming line in the Absaroka Mountains, near Cooke City, Mont.

There, at a ranch called the L-Bar-T, Hemingway spent many months throughout the 1930s hunting, fishing, riding, drinking and, of course, writing. There he developed some of the strongest relationships of his life, and there ended one of his several marriages. There Hemingway caught big trout, shot big bull elk, big bears, big mule deer and bighorn sheep.

He first came to the L-Bar-T in the summer of 1930, driving the very first automobile to make the trip from Cody, Wyo., over the Clark’s Fork River to Cooke City. With him was his second wife, Pauline, and his son Jack. When their car became mired on the wagon road, local rancher Lawrence Nordquist helped them out of the mud with a team of horses and took them to his home—the L-Bar-T. Hemingway had found his writing retreat in the high country.

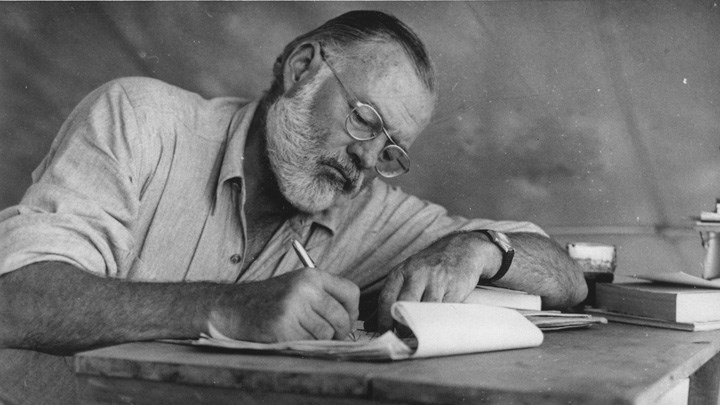

That summer Hemingway wrote much of his bullfighting novel, “Death in the Afternoon.” He also befriended several people from the area who would later become characters in his novels, particularly Chub Weaver, who remained a lifelong confidant. Hemingway fished the Clark’s Fork River regularly, drank copiously, rode horses daily and wrote incessantly. Despite the remote location, he provided regular written updates to his editor, Max Perkins, at Scribner’s back in New York.

By the end of summer, he was ready to hunt. It was during this first fall at the L-Bar-T that Hemingway shot his first and only bighorn sheep, taken from the slopes of Pilot Peak just west of the ranch. He wrote about the hunt for Vogue magazine saying, “The old ram was purple grey, his rump was white, and when he raised his head you saw the great heavy curl of his horns.”

Hemingway also killed his first elk that fall, a fine 6x6 bull, and encountered his first grizzly bears, “… their coats a soft bristling silver.”

With the birth of his third son, Gregory, in November of 1931, Hemingway and Pauline did not travel to Wyoming that year, remaining at their home in Key West, Fla. But in July of 1932 they set up housekeeping back in their old cabin at the L-Bar-T. That fall Hemingway tried for another bighorn sheep, this time with his friend Charles Thompson. In six days of hunting, Hemingway and Thompson failed to kill a sheep, with Hemingway later explaining, “Never got a shot at a ram—if you’re a good climber you could have got a ram. I’m not a good climber.”

When he wasn’t hunting, Hemingway was finishing “Death in the Afternoon,” sending his final proofs to Perkins by mail from the Cooke City General Store. On Oct. 11, Hemingway rode up the Pilot Creek drainage to a bear bait where he wounded a big black bear, necessitating following the 500-pound bruin in the gathering dusk and finishing it with a shot from 20 feet. Along with the bear, Hemingway downed two bull elk and a nice mule deer buck. But still no grizzlies.

It would be four years before Hemingway would return to the Wyoming high country. Africa and other places intervened. When he did return to Wyoming in 1936, he was writing one of his most famous novels, “To Have and Have Not.” In a letter to a friend he wrote, “Since we’ve been out here [at the L-Bar-T] I’ve written a little over 30,000 words … . Finished the section I’m doing today and am riding up to hunt tomorrow for three days. Maybe five.”

In September, Hemingway finally got his chance at a grizzly when his friends Tom and Lorraine Shevlin joined him at the ranch. With multiple grizzlies feeding on a bear bait, Hemingway and Lorraine approached as Tom watched nervously from a nearby hillside. “Papa could shoot a 30.06 like a machine gun,” according to Tom. Hemingway himself described the hunt in a letter to Perkins. “Last six days hunted Grizzlies and we got three and two good elk … .”

Hemingway later admitted to a biographer that Lorraine Shevlin was the inspiration for Margot Macomber in his African hunting story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Real people from Hemingway’s life often made it into the pages of his novels and short stories, sometimes to their chagrin.

After two years in Spain, Hemingway returned to the Wyoming ranch in August 1938 and wrote a portion of “For Whom the Bell Tolls” during his briefest stay at the ranch. Things were changing along the Wyoming/Montana line. The completion of the Beartooth Highway from Red Lodge to Cooke City, with its ensuing increase in traffic, annoyed Hemingway. His marriage to Pauline was failing. It rained incessantly and he hunted little during the two-month stay at L-Bar-T. He occupied his time working on the book and fleshing out its central character, Robert Jordan, who Hemingway decided hailed from Red Lodge, Mont.

By the summer of 1939, Hemingway had enough of the Cuban heat, where he’d been finishing “For Whom the Bell Tolls” at his Havana home, “Finca Vigia.” To escape the heat, he arranged for his sons and Pauline to join him at the L-Bar-T. Hemingway undoubtedly knew this would be his last autumn in Wyoming. He wrote a story for Vogue that year called “The Clark’s Fork Valley, Wyoming” that summed up the treasured experiences, including all the unforgettable hunts he, his family and friends enjoyed there. He soon divorced Pauline, married fellow writer Martha Gellhorn and found a new mountain home in Sun Valley, Idaho.

In a eulogy Hemingway wrote for a Sun Valley friend, many people believe he summed up his own life with the words, “Best of all, he loved the fall … .”

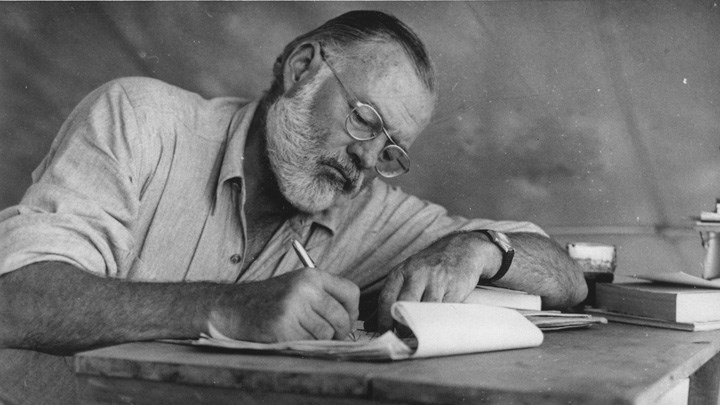

Editor’s Note: American novelist, short-story writer, journalist and avid hunter Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in May 1952, a month before he left for his second hunting trip to Africa, and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954. His succinct prose style and adventurous lifestyle exerted a powerful influence on American and British fiction in the 20th century with many of his works labelled classics of American literature. Born in July 1899, Hemingway passed away 60 years ago this month on July 2, 1961, at the age of 61.

About the Author

Keith R. Crowley is an award-winning writer and photographer and the author of three books on the outdoors: “Gordon MacQuarrie: The Story of an Old Duck Hunter” (2003), “Wildlife in the Badlands” (2015) and “Pheasant Dogs” (2019). When he is not traveling in search of new stories and images, you can find him at his home on a lake in northwest Wisconsin with his wife, Annette, and a collection of old dogs and old boats.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.