by Brad Fitzpatrick - Thursday, April 2, 2020

By now you’ve almost certainly heard of the breakout Netflix docuseries “Tiger King” which follows the bizarre series of events that led to (spoiler alert) Joseph Allen Maldonado-Passage receiving a 22-year prison sentence for violations of the Lacey Act and the Endangered Species Act, as well as a murder-for-hire plot. Maldonado-Passage, better known as Joe Exotic, is the former owner of the Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park in Oklahoma where more than 200 tigers and other exotic animals were kept on display at one of the largest roadside wildlife attractions in the nation. It’s impossible to touch on all of the outrageous storylines that unfold in the series, but a few of the more notable themes include Joe Exotic’s run for governor of Oklahoma and president of the United States, his music career and his complex love life.

The central thrust of the series, however, centers around Joe Exotic’s relationship with tigers and his toxic feud with Carole Baskins, CEO of Florida’s Big Cat Rescue. Baskins and Joe Exotic went to great lengths to ruin one another’s lives, and the two outsized figures hurl insults back and forth throughout the series regarding the other’s treatment of big cats.

“Tiger King” is certainly entertaining and is chock-full of moments that are sure to leave even the most jaded viewer stunned by the outlandish plot twists. But while the show offers a reprieve from the banality of being locked in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s not about conservation.

Tigers, lions, bears, cougars, elephants and other charismatic species capture our attention in a way that no other animals can. After all, if Joe Exotic were raising emus instead of tigers this story wouldn’t have the—pardon the pun—teeth that it does. Many Americans say they care about wildlife, but few have a good understanding of how conservation really works. “Tiger King” entertains, but it doesn’t educate.

So, what are the real threats facing wildlife? Habitat loss, poaching and retaliatory killings, primarily. The fact that there are just 3,900 tigers left in the wild is less a product of them being “hunted to extinction” (India closed hunting in 1972) and more about unchecked human population growth and loss of habitat. Tigers are being forced to live in smaller and smaller areas fringed by people, and many tigers are killed each year when they cause problems for their human neighbors. Last year India lost multiple tigers to poachers and angry villagers who rigged power lines to electrocute passing cats. What’s more, the bones of tigers and other big cats are being used for medicinal purposes in Asia, and the World Wildlife Fund fears that the domestic trade in tigers is fueling the demand for bones—and placing wild cats at undue risk. And tigers aren’t the only species facing threats from human population growth and illegal, unregulated killing.

These issues aren’t addressed in “Tiger King.” To be fair, the producers never painted this as a conservation-based series but rather a look at some of the more vivid personalities in the big cat biz. But what “Tiger King” should teach us is that many people have a poor understanding of the critical conservation needs of the world’s wildlife and how to effectively address those needs.

Why the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Works

Real conservation provides habitat for wildlife and utilizes science-based management techniques that seek to preserve the health of game populations. And, for over a century, the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation has been doing just that. Hunters understand that wild animals need wild places, and its thanks to the efforts of hunters that many species have survived. For example, the projects of the hunter-backed organization Ducks Unlimited protect more than 10 million acres across North America, much of it serving as vital nesting ground for wetland bird species that were nearly exterminated during the market-hunting years. The whitetail deer was once scarce across the country and was completely absent in states like Kansas and Indiana, but hunter-funded wildlife conservation efforts brought deer back from the brink of extinction. By setting seasons and bag limits, states can scientifically manage their own deer herds through legal, regulated hunting, and hunters’ dollars pay for research projects and public lands. It’s not just deer that have thrived, though. Hunters have helped populations of pronghorn antelope, wild turkey, elk and other game species. What’s more, by preserving habitat, hunter dollars also improve the health of ecosystems, and that is a benefit to non-game species.

In 1937 the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, which placed an excise tax on hunting and shooting products for conservation funding, was signed into law. Since then, hunter dollars have provided more than $11 billion toward wildlife conservation. Additionally, the sales of licenses and permits bring in millions of dollars for state wildlife agencies each year and incentivize those states to properly manage wildlife numbers. In truth, every hunter who purchases a license is doing more for wildlife conservation than the people who utilize species like tiger for profits.

How Hunters’ Role in Wildlife Conservation Plays Out Beyond U.S Borders

Hunting doesn’t just help wildlife in the United States. Around the globe, countries have utilized the same principles from the North American Model to help protect game. Many “conservationists” who have been duped into thinking that hunting is the root of all conservation ills attack the sport without understanding how and why it works for wildlife. In Africa, countries like Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Mozambique and other nations have established hunting industries that provide the lion’s share of conservation funding in rural areas. Namibia’s communal conservancies have placed the impetus for wildlife management in the hands of local people. In this way, rural villagers see direct financial profit from wildlife and are incentivized to preserve game populations and vital habitat. The dollars hunters spend in communal conservancies help protect wildlife and provide a living wage to thousands of people. This money has helped fund rural schools and hospitals and reduces the need for local people to poach.

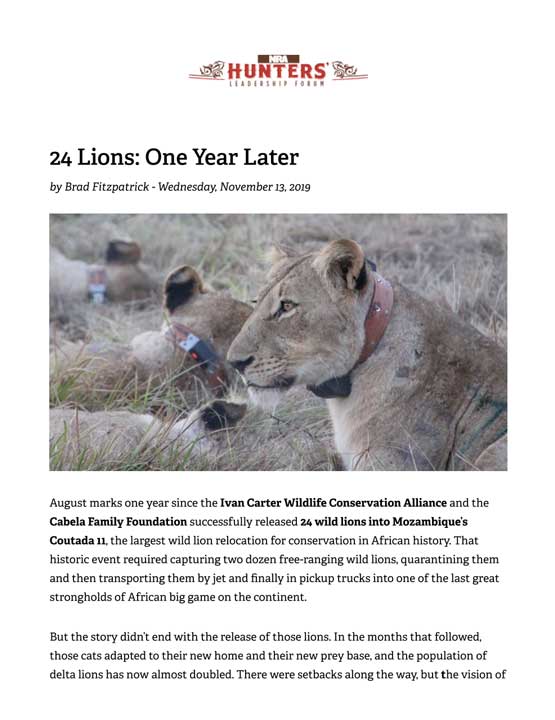

In 2018 the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance and the Cabela Family Foundation funded the “24 Lions” project which oversaw the relocation of 24 lions from South African game reserves to the 2.5 million-acre Zambeze Delta in Mozambique. Those cats are projected to represent 10 percent of the entire world population of wild lions by the year 2050, and the ambitious project was made possible by hunters. How? Hunting dollars restored the delta to its former glory following Mozambique’s gruesome civil war and hunter contributions also funded the expensive and complex 24 Lion operation. While on a charter flight from Beira, Mozambique to the delta to cover the project, I flew over tens of thousands of unprotected acres that had been burned for agriculture and ranching. Only the delta, which is protected by hunter dollars, was intact.

These are just a few of the stories that highlight real conservation successes. “Tiger King” is entertaining, but it’s not about conservation. The real conservationists are those who improve wildlife habitat and protect populations, and that’s hunters.

Editor’s Note: The NRA Board adopted the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation as official NRA policy in December 2014. That same month, under the NRA presidency of Jim Porter, the NRA established the NRA Hunters’ Leadership Forum (HLF) to work alongside the NRA's Institute for Legislative Action (NRA-ILA) to fight the culture war on hunting and address the political, demographic and technological challenges facing the future of hunting and wildlife conservation in the 21st century. In 2016, NRA Publications launched this NRA HLF website, NRAHLF.org, to monitor the issues impacting hunting’s future while telling the story of hunters and hunting and where our dollars go.—Karen Mehall Phillips, Director of Communications, NRA HLF

About the Author:

Brad Fitzpatrick is a full-time freelance writer living in Ohio. His works have appeared in several NRA publications and he has hunted on four continents. Fitzpatrick competed on his university's trap and skeet team and has served as an instructor for 4-H Shooting Sports. He's also passionate about conservation, particularly hunter-funded projects both in the United States and abroad.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.